Assemble your life action by action: the timeless approach to doing big things and keeping your sanity

A few years ago I went back to school. Each semester, including summers, I would take a double course load. The goal was to earn my degree in two years. (At one point in 2018 I was taking eight classes simultaneously.) I also worked full-time. Stress was constant and it occasionally felt like panic. I remember thinking, at times, this is too much. I’m not going to be able to do all of this in two years. What if it’s all for nothing?

Around this time I read one of my favorite ideas from Marcus Aurelius: “You can assemble your life action by action, and no one can prevent that.” Even ants and spiders go about their day putting the world in order as best as they can, he chided himself. “And you’re not willing to do your job as a human being? Why aren’t you running to do what your nature demands?”

This floored me. Why was I working myself up by thinking about all the things I still had to do? Why was I exhausting myself with what-ifs?

“Don’t let your imagination be crushed by life as a whole,” Marcus Aurelius told himself. “Don’t try to picture everything bad that could possibly happen. Stick with the situation at hand, and ask, ‘Why is this so unbearable? Why can’t I endure it?’ You’ll be embarrassed to answer.”

It was also around this time that I learned “the process” that seven-time national champion football coach, Nick Saban, teaches his players. He found that the average football play lasts about seven seconds. Don’t think about winning a national championship, he tells his players. Don’t think about winning the game. Don’t think about what the scoreboard says. Focus on your inner scoreboard. Focus on executing the current play to the best of your ability. As long as you focus on the inner scoreboard, the outer scoreboard will take care of itself.

In other words: I didn’t have to feel overwhelmed! I didn’t have to think about all the assignments and classes I’d yet to complete. I didn’t have to think about graduating. I didn’t have to think about careers. I didn’t have to work late into the evening! I only had to do two things each day: 1.) Focus solely on the work in front of me and 2.) Complete a few key tasks. That’s it. I could let time, over the long term, do the heavy lifting. I would provide consistent, small steps. Time would turn those small steps into larger accomplishments.

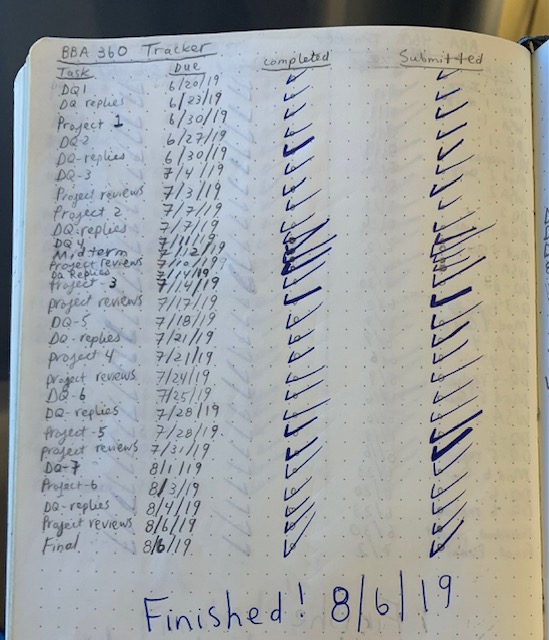

Below is a page from my 2019 planner. For each class, I’d write the assignments and their due dates. My only focus was on completing assignments and submitting them. This kept me focused and gave me the satisfaction of seeing visible progress.

You can do your work as nature requires, Marcus Aurelius said, by working…

Without frenzy or laziness

Without delving into other’s affairs

Focused like a Roman on the task at hand

While always asking, is this essential?

Calmly, steadily, and with no loose ends.

This is a great example of slow productivity.

It’s also a great example of a classical adage I love: Festina lente…

Make Haste, Slowly

“By any reasonable standard, [John] McPhee is productive,” writes Cal Newport. “He’s published 29 books …. And yet, he rarely writes more than 500 words a day. When asked about this paradox, McPhee famously quipped: ‘People say to me, ‘Oh, you’re so prolific’…God, it doesn’t feel like it—nothing like it. But, you know, you put an ounce in a bucket each day, you get a quart.’”

Author Ryan Holiday is one of the most prolific writers of our generation. He’s written around a dozen books in 10 years (not to mention his countless other business and writing obligations). What’s most inspiring is that he still makes it home every day for dinner and evenings with his family. (After all, he reasons, how successful are you really if you can’t spend a lot of time with your family?)

How does he do it?

He explains that it’s a simple commitment to small, daily habits. “Two hours a day of writing may not seem like much,” he says, “but 2 hours a day for ten years adds up.” When he sits down to work on a book, his goal is not ‘finish the rough draft’, or ‘write until noon’—his goal is simply: ‘Write section 2 of chapter 3’. He doesn’t work on whims. There’s no time for toiling away in open-ended slogs.

This idea is captured beautifully by Billy Oppenheimer, who recently wrote about Naval Ravikant’s approach: work like a lion. “The way people tend to work most effectively, especially in knowledge work,” says Naval, “is to sprint as hard as they can…and then rest.” Billy adds, “It’s like a lion hunting, [Naval] says: sit, wait for prey, sprint, eat, rest, repeat. The way to work most ineffectively is to work like a cow standing in the pasture all day, slowly grazing grass.”

Asked by his editor how he planned to write his epic novel East of Eden, John Steinbeck replied, “One foot in front of the other … Just get my two pages written every day. That’s the best and only thing I can do.” When his editor joked that he should increase his daily word rate, Steinbeck didn’t find it amusing. “I like to hold the word rate down because if I don’t, it will get hurried and I will get too tired one day and not work the next. The slow, controlled method is best.” He said he would not “permit himself the indiscipline of overwork. This is the falsest of economies.”

When the Duke of Milan questioned Leonardo da Vinci about his seeming procrastination in painting The Last Supper, Leonardo explained, “Men of lofty genius sometimes accomplish the most when they work the least, for their minds are occupied with their ideas and the perfection of their conceptions, to which they afterwards give form.” In Several Short Sentences About Writing, Verlyn Klinkenborg put it perfectly: “You can’t think all your best thoughts in advance.” Success happens when you keep showing up, keep applying pressure.

We don’t have to trade sanity for excellence. We can take it action by action. We can make haste, slowly.