This is the main thing I learned in CPR training—and it applies to everything else

A few weeks ago, my wife, Courtney, stabbed herself.

She meant to stab the sweet potato in her hand, but missed. The point of the steak knife plunged into the meaty part of her left palm, above her wrist, and a geyser of blood shot across the kitchen island.

I went from innocently peeling the shell off a hard-boiled egg to feeling absolute terror in a matter of seconds.

Courtney—who never even tells me when she has a headache, let alone goes to the doctor for anything that isn’t absolutely necessary—pushed a dish towel into the gash and calmly said, “We have to go, now.”

I didn’t know where she’d cut herself—if she’d sliced open her wrist or hit something important. All I could think was that the human body only holds six pints of blood (which I now know isn’t true; it’s closer to ten) and that she was bleeding badly.

I ran to the garage and yelled, “Get in the car!” I had the wherewithal to grab her ID, but that was it. I didn’t even put shoes on. I flew out of the driveway and broke approximately fifteen traffic laws in the two miles between our house and the ER.

I slammed the car into park at the entrance and rushed her through the sliding doors. Shaking and out of breath, I asked a nurse in the lobby to take a look. As she pulled off the towel, I warned her to be careful; blood might still be squirting. I cringed as I looked to see how bad it was and… it actually didn’t look too bad. The dish towel was soaked end to end in blood, but the bleeding had stopped.

Maybe I had overreacted.

A doctor saw us within twenty minutes, cleaned out the wound, patched it up, and sent us on our way.

When we got home, I replayed everything in my mind. Why had I run around like a chicken with its head cut off? Why was I so unprepared? I felt guilty. I decided never again would I feel so helpless. There’s no excuse for not being prepared. So I watched videos on the Heimlich maneuver, bought a LifeVac travel kit, a second fire extinguisher, and hemostatic gauze, and signed us up for a CPR/First Aid class at the Red Cross.

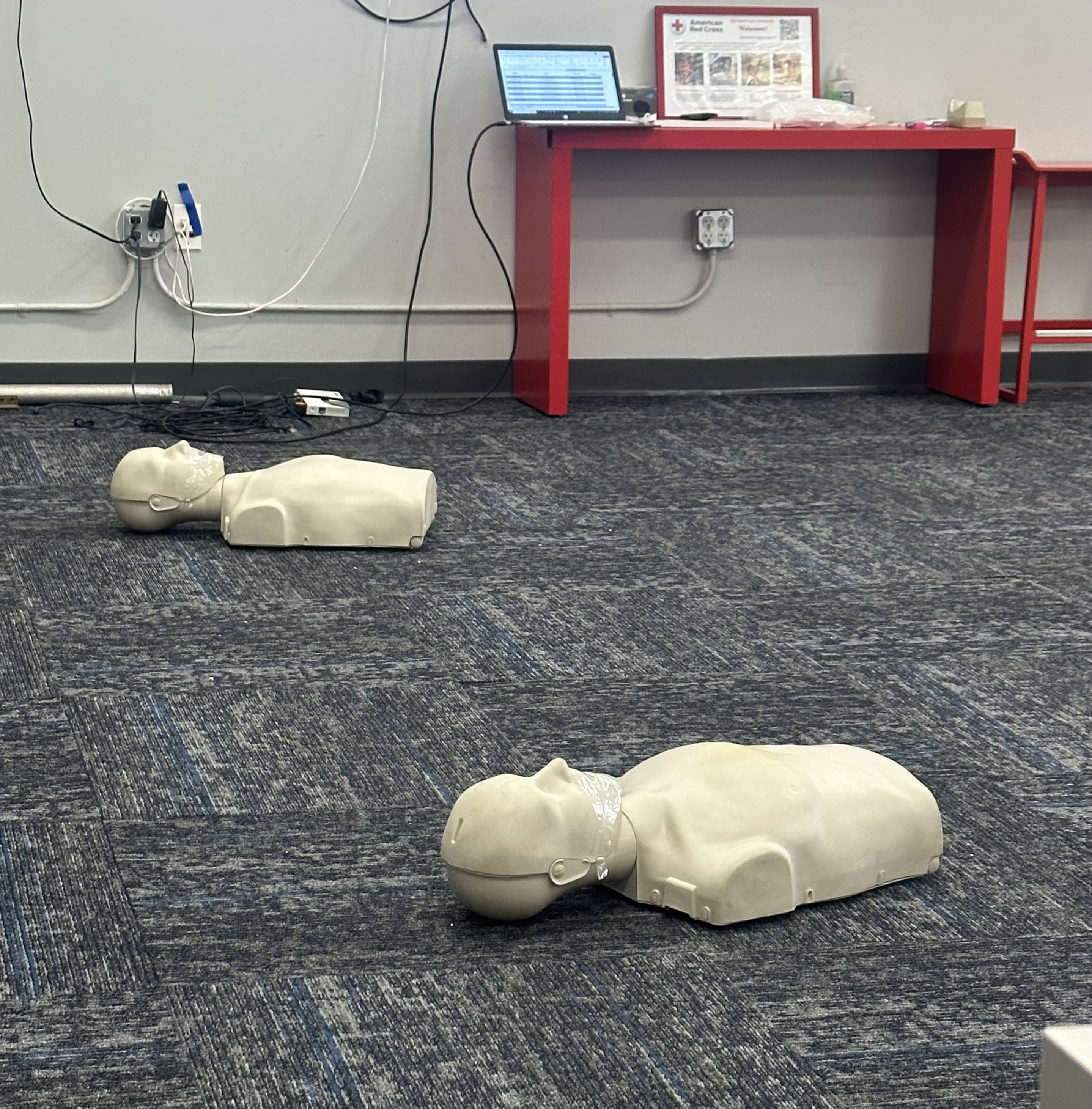

The class was three and a half hours long, and there were nine other students. On a wall-mounted TV, the instructor played the first video: how to properly wash your hands. Courtney turned to me and whispered, “You owe me for this.”

After that, the instructor briefly discussed the material we would learn. She warned that if you save someone’s life, don’t let them repay you with, say, a steak dinner. This could lead to a lawsuit. Courtney grabbed the pocket journal I brought to take notes and wrote, “Do not accept steak dinners.” I had to bite my tongue to keep from laughing.

The next video showed an elderly woman having symptoms of a heart attack. “Honey, what’s wrong?” her alert husband asks. “I’m having chest pains,” she replies. “No, no, no, this isn’t happening,” he moans. Just then, their son—clearly the hero—enters the room.

My journal open, pen at the ready, I leaned forward. Here we go. The secrets of how to save a life were about to be revealed and I, Emily Yaskowitz, would henceforth be prepared to do just that—save lives. What’s the son going to do? I thought. What at-home machine has he invested in that will now pay off and save her life? What tricks would he perform?

The son asks his mom what’s wrong. “I’m having pain in my chest,” she winces. Turning to his dad, the son says, “Call 9-1-1.” He turns back to his mother. “Here,” he says, “chew these aspirins.” The woman chews and rubs her chest while they wait for help. When the first responders arrive, they load her onto a gurney and send her away in an ambulance. The dad is overwhelmed with gratitude. “Son, I don’t know what I would have done without you.” The video ends.

By this point I wanted my money back.

Forty-five minutes in and we’d learned not to accept gifts and to call 9-1-1 in an emergency.

Over the next few hours, though, we practiced CPR on dummies, tied tourniquets, and learned what to do if someone is having a seizure or going into shock. Still, most of what we talked about wasn’t new. By the time the class was over, I realized that was the whole point.

I recently read that Minnesota Vikings head coach Kevin O’Connell briefly played quarterback in the NFL. He threw six passes as a New England Patriot and was cut after one year. He then signed with the Lions and was traded five days later. He auditioned for teams constantly, and it rarely went well. As Seth Wickersham writes, “He always wanted to create ‘the wow factor,’ […] an exceptional throw that would make a team believe. ‘I learned that’s the last possible thing you should do,’ he says now.”

He learned that good quarterbacking involves taking care of the mundane. “He watched Brady and Joe Montana execute game-winning drives in the Super Bowl. What stood out was how unspectacular they were when the stakes were the highest. ‘If they called the same play in the middle of spring practice, they would have executed it the same way,’ [O’Connell] says. ‘They weren’t trying to do anything other than just play the position consistently at a high level.’”

That’s what I learned in the CPR class. It’s about executing the basics—preparing and practicing.

“We don’t rise to the level of our expectations,” the Greek poet Archilochus said. “We fall to the level of our training.”

It’s not about dramatic heroics, but consistent steadiness.

That’s true in the ER, and it’s true everywhere else.

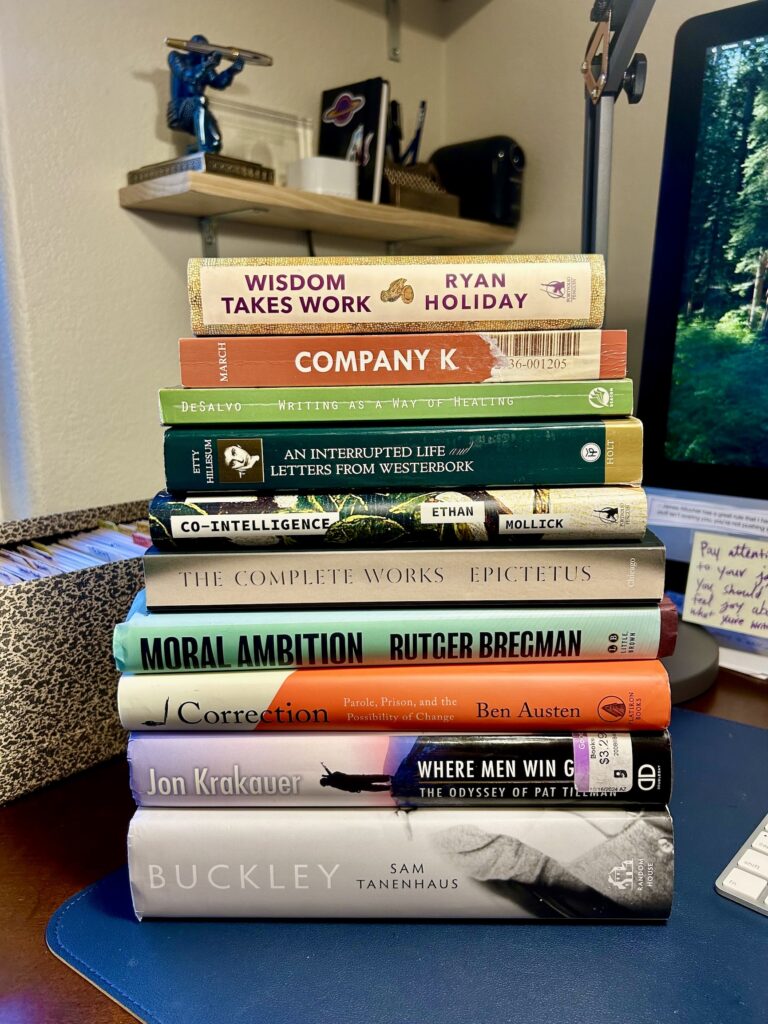

No matter how many influencers or life hacks there are, I’ve yet to find a better prescription for a good life than this: go to bed early, get up early, journal, read, exercise, do the right thing, care about others, and eat decently.

Do these things consistently and in a few years you’ll be a different person.

But that’s the thing: we already know this. The problem is that it’s terribly unsexy. It’s boring. That’s why there’s always a new life hack or mud cleanse or cage-free yoga class or whatever.

It’s why someone will attend a self-help seminar or watch motivating YouTube videos and still never change. The important stuff is often so straightforward—like calling 9-1-1 or calmly applying pressure to a wound—that it can be easily overlooked.

We know we should save and invest—that fortunes aren’t made from windfalls but from small, consistent savings. We know we keep our job not because we have a revolutionary idea, but because we show up each day and stay steady. “Your teeth don’t not rot because you go to the dentist twice a year,” Simon Sinek said. “They don’t rot because you brush them for a couple minutes every day. It’s the little things adding up over time.”

Four years ago I could barely run half a block without stopping. Last week I spontaneously ran a 4.5 mile route—one I’ve never run before—in a little over a half hour, and I could have kept going. And I’m not saying that to sound impressive, because it’s not impressive. What else is supposed to happen when you run three to four miles a day, four days a week, for four years, while gradually increasing your speed?

I fell to the level of my training.

Bob Dylan didn’t wake up one morning and write “Blowin’ in the Wind” because genius struck. “These songs don’t come out of thin air,” he said. “If you sang ‘John Henry’ as many times as me—if you had sung that song as many times as I did, you’d have written, ‘How many roads must a man walk down?’ too.”

He sang the same old songs so many times that when he began to write his own lyrics, he felt like he “was just extending the line.”

He fell to the level of his training.

Feeling confident in an emergency is less about skill than preparation. You don’t need to know how to perform an emergency thoracotomy, but you should have the Heimlich maneuver down pat. You should be prepared enough that if an emergency happens, you can keep your head and assess the situation calmly—exactly the opposite of what I did when I showed up at the ER in my socks.

This matters in big things and small ones. Brilliance and willpower are unreliable.

We fall to the level of our training.

That’s true in an ER lobby. It’s true in your finances, your career, your whole life.

It comes down to doing the most important, basic things consistently.

Go to bed early.

Get up early.

Journal.

Read.

Move your body.

Tell the truth.

Do the right thing.

Go easy on the sweets.

Simple.

Far from easy.

But simple.