9 lessons I’ve learned from 10 years in a relationship

My wife and I celebrated our 10th anniversary this month, and as a gift, I made a little scrapbook of our first 10 years together.

Looking at our first photos—the scraggly, 25-year-old me beaming next to my then-girlfriend—I thought to myself, wow, Emily, you were so clueless.

I spent this month thinking about what makes a relationship work and grow, and what I learned through my own experience.

I came up with a list of 9 lessons I’ve learned from 10 years in a relationship:

1. Ego is the cause of most relationship problems

If I had known the power of humility when I was 25 years old, I would have saved myself years of trouble.

Almost all relationship problems are solved with a genuine I see where you’re coming from. I would feel the same way if I were you. I was wrong. I’m sorry.

It took me a while to feel comfortable saying sorry, but I say it all the time now. It’s great. I say sorry almost too much. (I say almost because every once in a while, when the wind blows in from the east and the sun is shining just so, I’m not completely wrong.)

2. Listen like a best friend

Our partner is supposed to be our best friend. And best friends are inherently good listeners: comforting, helpful, and quick to take our side while also trying to be objective.

We do this too in our romantic relationships. When your partner is venting, you listen like a best friend. You validate their right to be irritated about the crap they had to deal with that day. You throw in a few well-timed hmms and reassuring touches. You describe a similar experience you’ve had so they don’t feel so alone.

But what if the reason your partner is frustrated is because of you?

It’s here where listening and camaraderie are replaced with defensiveness and rebuttals. At least that’s how it was for me. The more I was confronted with my bullshit, the louder the voice in my head screamed that she was ridiculous and harsh.

But, of course, it was me who was ridiculous and harsh, because I wasn’t listening.

Chances are good that your partner isn’t trying to fight. Chances are good they simply want to express a valid feeling to the person they rightfully expect to feel comfortable expressing it to.

Listening like a best friend to your partner’s frustrations even when they’re about you can feel impossible. But it just takes practice. I would know, I’ve had years of it. Courtney has had to have plenty of tough conversations with me about taking accountability, being on time, not staring at people, etc. And I’m grateful for this because it means she cares.

Again, it’s not easy, but it’s what a best friend would do.

3. The 100/0 Rule

This may sound extreme, but a relationship is not 50/50.

A relationship is 100/0.

You have to give everything and expect nothing. It’s the only way.

4. Disagreements are inevitable, arguments are optional

One day at work about 8 years ago, I was talking to a coworker I looked up to and wanted his advice.

“You know how when you’re arguing with someone and—”

“Whoa, whoa, whoa,” he laughed, putting his hands up. “ I don’t argue with anyone.”

I immediately wanted to argue with him. How can you go through life without arguing? Wasn’t that part of it?

Instead of voicing my confusion, I asked him what he meant.

“It’s simple,” he smiled. “I just don’t argue.”

“But what if you disagree with someone?”

He shrugged. “Then I disagree. Look, if I’m open to hearing what someone has to say, I’ll listen. But—and here’s the important part—before I jump into what I want to say, I first ask them if they’re willing to listen. If they are, cool. If they’re not, no problem. At least I didn’t waste my time talking in vain.”

This was the wildest thing I’d ever heard in my life.

It was also a huge relief: I never have to argue with anyone again!

Who would have thought you could simply state your point, let the other person state theirs, and do this back and forth without raising your voice or becoming frustrated?

Arguing can feel natural, but it’s not. What’s natural is cooperation. What’s natural is finding common ground for the common good.

5. Yes! as a default response

In 10 years, there’s been maybe a handful of times (mostly at the beginning of our relationship, mostly involving hiking) that I’ve said no to something Courtney wanted to do together.

Whenever she asks if I want to do something with her, my response is almost always yes! Even if I don’t have much interest in it, I say yes. And I try to be enthusiastic about it.

Want to go to the grocery store together? Hell yeah. Want to work on a 1,000-piece puzzle? Ab-so-fruitly. Want to re-re-redecorate the bathroom because the decorations have become stale and the wall color is boring and don’t I agree? The…ohhh yes, right, the wall color. Bathroom. Boring for sure. I definitely noticed. Let’s do it!

I do this for two reasons: Because I love hanging out with her and because life is offensively short. At the end of my life, whether today or tomorrow or 80 years from now, I know that I will give anything for one more car ride, one more evening routine, one more anything with her. I try my best to remember that and live by it.

6. Conserve your energy

The other day, Courtney and I were watching a show where this engaged couple was in a heated discussion, trying to get on the same page. It ended when the guy walked away saying, “I don’t have the energy for this.” All I could think was, Bro, what the hell else are you using your energy for?

Most of what we do is inessential, and we drain precious time and energy doing it.

You had the energy to follow sports updates and bet on the games, but none for a meaningful conversation with your partner? C’mon. You followed breaking news and now you’re too frazzled to greet your partner with a smile when they get home? That’s not fair.

I used to misplace my attention like this all the time. No one I knew was further along in Candy Crush than me (making me a winner and a loser at the same time).

Once I learned how to ruthlessly eliminate the inessential and be still, I grew as a person and partner.

7. Keep it playful

It’s not that serious. Be goofy and silly together. Laugh at yourself. I swear I never laugh harder than when Courtney roasts me. I even write down her roasts of me on notecards and read them later when I want a good laugh.

8. Follow through

If you say you’re going to do something, do it. And if there’s a chance you might not do it, don’t say you’re going to. Better still: just do the thing and don’t talk about it.

9. Fill your home with virtue

I almost didn’t include this one because it sounds kind of corny, but I decided it’s too important to leave out: a house filled with virtue is more beautiful than a house filled with gold.

Selflessness, transparency, honesty, laughter, spontaneity, routine, love, calm, kindness, acceptance, patience—fill your house with these things and you will have the most beautiful, joyful dwelling in the whole world. You’ll have the most beautiful, joyful relationship too.

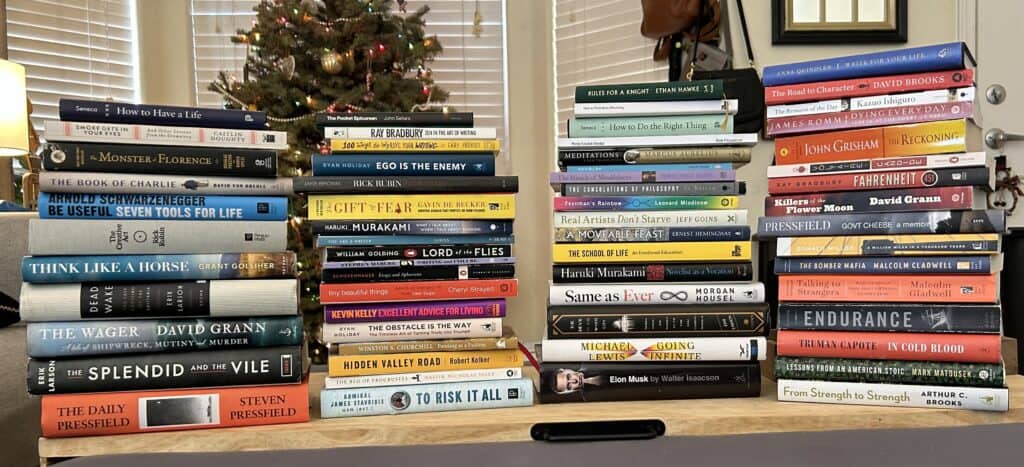

Books read this month:

-My dad gave me his copy of A Confession by Leo Tolstoy and it’s one of the best books I’ve read. It’s answered some of the questions I’ve had for years about religion and faith. If you’re even a little curious, it’s well worth the read. And if you haven’t read his A Calendar of Wisdom, you need to!

–On Writing by C.S. Lewis. A compilation of writing advice from one of the best. My biggest takeaway: reading a book just to get to the end is vulgar. The whole point is to enjoy the book as you read. I thought about this the other day when Courtney and I planned to go for a hike and then go out to eat afterward. I was excited, but mostly about the food part. The hike was something to get through. Lewis would call this vulgarity. By thinking of food as the payoff, I was thinking about, well, the payoff. But thinking about a payoff cheapens life. There is no eventual payoff. The payoff is this moment, right now. Besides, everything we do—the stuff we like and dislike—it all passes by anyway. We’re here for a short time and then the lights go out. Don’t wish away a second of life by anticipating something else. There is no something else. This is it. Don’t forget to live.

-I first read Keep Going in 2021 and I decided to read it again because I love Austin Kleon. He posts his work on social media every day—a journal entry or a collage or a pile of vinyl records he melted in the sun—the message being that’s important to create for its own sake. He recently inspired me to start a collage journal of my own and I’m having a lot of fun with it.

–William Blake vs. The World by John Higgs. I knew nothing about William Blake before reading this, and WOW, what a phenomenal book. Tons of thought-provoking ideas on imagination. I especially loved the parts about human perception and how, outside of the human mind, we have no idea what the universe looks like. Whoa.

–David Sedaris Diaries: A Visual Compendium by David Sedaris. I’ve been a fan of David Sedaris for about 20 years now and decided to give his mostly visual book a read. I LOVED it. If you get inspired by looking through people’s journals and diaries like I do, you will love it. It’s a compilation of pictures of and passages from the diaries he’s kept throughout his life. I was inspired by the way he finds trash on the street and turns it into art. Or turns it into nothing and simply binds it in his diary as is. Because he realized, he explains, that when he sat down at his desk to write in his diary, “I could really do whatever the f— I wanted.”