Take a Closer Look

Look at your fish

In 1864, a young man named Samuel Scudder arrived at Harvard to interview with the celebrated biologist Louis Agassiz. He likely expected a conventional test—something meant to measure what he knew, or to probe his intellect.

Instead, Agassiz placed a preserved fish in front of him and gave a single instruction: “Look at your fish.” Then he walked out of the room.

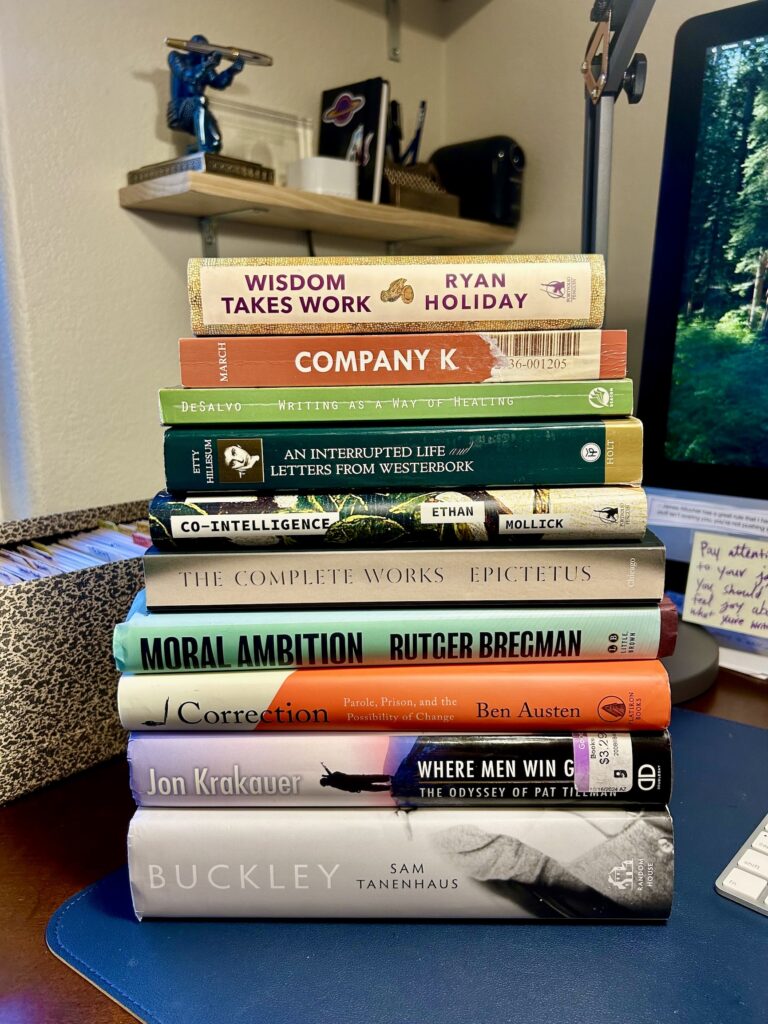

As Ryan Holiday writes in Wisdom Takes Work, hours passed. Scudder fought boredom. He examined the fish from every angle he could think of. He handled it, turned it over, traced its contours, counted its scales. Maybe it was a test of patience. With nothing else to do, he drew it.

When Agassiz returned, he was unimpressed. He told Scudder that he hadn’t truly seen the fish yet and urged him to look again. Then he left.

This pattern continued for days.

Each time Agassiz returned, he asked what Scudder had observed. Each time, the answer fell short. Eventually, Scudder could only admit the truth: “I see how little I saw before.”

That admission marked a turning point. After another long stretch of uninterrupted looking, something finally clicked. Scudder began to notice the fish’s underlying order—its symmetry, the way its organs mirrored one another on both sides. When he offered this observation, Agassiz responded with enthusiasm: “Of course! Of course!” When Scudder asked what he should do next, Agassiz replied, “Look at your fish.”

In the end, Scudder discovered… well, nothing.

But as Scudder later explained, “it was a deeper lesson,” Ryan writes, “perhaps the most important one he ever got in his career as a scientist: the power of focus. The importance of intensely looking, with dedication and without interruption, at something as simple and ordinary as a fish in order to truly see it. It was, [Scudder said], ‘a lesson whose influence has extended to the details of every subsequent study; a legacy the Professor had left to me, as he has left it to many others, of inestimable value, which we could not buy, with which we cannot part.’”

David McCullough uses this story in his writing classes. “Seeing is so important in this work,” he said. “Insight comes, more often than not, from looking at what’s been on the table all along, in front of everybody, rather than from discovering something new. Seeing is as much the job of a historian as it is of a poet or a painter, it seems to me. That’s Dickens’ great admonition to all writers, ‘Make me see.’”

Nobody bothered to look closely enough

David McCullough recalls his own Agassiz Jr. moment while writing Mornings on Horseback. He was trying to understand what had caused Theodore Roosevelt’s severe asthma attacks as a boy—episodes so intense they sometimes left his family fearing for his life.

McCullough consulted physicians. One asked whether there had been a cat or dog in the house, or whether the attacks coincided with pollen season. A psychosomatic specialist wondered if they happened around emotionally charged events like birthdays and holidays.

Using young Theodore’s diary entries, McCullough made a calendar of what he did each day. “In pencil, I wrote where he was, who was with him, what was going on, and in red ink I put squares around the days of the asthma attacks. But a little like Scudder and the fish, I couldn’t see a pattern.”

Then one day, as he looked at the calendar on his desk, he noticed something: every asthma attack happened on a Sunday. McCullough asked himself what Sundays meant in Theodore’s childhood. And then the answer became clear. If Theodore had an asthma attack on Sunday, he didn’t have to do something he hated: go to church. Instead, he got to go to the country with his father—just the two of them. For young Theodore, this was heaven.

This didn’t mean that the asthma attacks were planned, but the anxiety brought on by the prospect of going to church likely triggered them. (A high price to pay, because the attacks were horrible.) Other things may have contributed to the attacks, but the Sunday pattern was too pronounced to be coincidental.

“The chances of finding a new piece are fairly remote—though I’ve never written a book where I didn’t find something new—but it’s more likely you see something that’s been around a long time that others haven’t seen. Sometimes it derives from your own nature, your own interests. More often, it’s just that nobody bothered to look closely enough.”

What had been there all along

DNA is the master cookbook of who we are and how we function. Its sibling, RNA, is the messenger. RNA tells our cells what to do.

In the early 1980s, scientists had discovered something crucial: RNA could replicate itself—by itself. “If some RNA molecules could store genetic information and also act as a catalyst to spur chemical reactions,” Walter Isaacson explains, “they might be more fundamental to the origins of life than DNA, which cannot naturally replicate themselves without the presence of proteins to serve as a catalyst.”

In 1998, biochemist Jennifer Doudna was on a mission: to show how, exactly, RNA could replicate itself. First she would need to know what an RNA model looked like. Back in the 1970s, researchers had mapped the structure of smaller, simpler RNA molecules. But when it came to larger RNAs, progress stalled. For nearly twenty years, scientists found it difficult to isolate them clearly enough to understand their structure. “Colleagues told Doudna that getting a good image of a large RNA molecule would, at that time, be a fool’s errand.”

But if she wanted “to understand the workings of a self-splicing piece of RNA, she would have to fully discern its structure, atom by atom”—something most scientists at the time believed would be too difficult, if not impossible, to do. “Hardly anyone was trying anymore,” famed biologist Jack Szostak recalls.

It took two years, but Doudna and her partner, Jamie Cate, did it. They produced a working model of the structure of an RNA molecule—work that would eventually lay the foundation for CRISPR, the most widely used gene-editing system today.

When they started, RNA was old news. But by giving it sustained, almost stubborn attention, they discovered something entirely new.

It hadn’t been impossible after all. It’s just that no one else bothered to look closely enough at what had been there all along.