46 ideas to revisit again and again and again

Sometimes I forget important things I’ve learned.

I’ll jot down an insight and then rush to the next thing. It’s so much easier to go, go, go than it is to slow down.

But like food, wisdom does us no good if we just consume it. We have to break it down, digest it. It must become part of us.

So I spent time reviewing my journals from this year, revisiting what I’ve learned, and reflecting on the ideas that have most inspired and changed me. If something we learn doesn’t become more valuable the better we understand it, I’m not sure it was worth learning in the first place.

Said differently, the best ideas must be constantly revisited, reexamined, and reapplied to our lives.

That’s why I made this list of 46 ideas worth revisiting again and again and again…

- A calm, tranquil mind = happiness. In all things, make tranquility your aim. If a thought is agitating you, stop thinking about it. If an action needs to be calculated or will cause you to worry, don’t do it.

- People rarely fear what they should. We fear losing our jobs…not about whether we’re doing something meaningful. People are afraid of immigrants…not that they’re short of breath climbing a flight of stairs. We’re afraid to start…not that we might not start. We’re afraid of dying…not afraid of never truly living.

- The true measure of wealth is how much time you’re able to spend with the people you love most. Plenty of people are successful in business. Millions of people drive fancy cars. That stuff is easy. What’s harder is to moderate the impulse for more, to rewire the programming that says you’re not successful unless you make this much money or earn that coveted title. Being able to take a random afternoon off and go hiking with my wife, that’s living the dream. Besides, who’s wealthier: the millionaire who’s always dashing off to “pressing” obligations? Or the person who says, sorry, you can’t afford my hourly rate? Because that’s the other measure of wealth: how many things you can afford to say no to.

- Don’t think about how long it will take. Just make a little progress each day.

- Where can you eliminate the inessentials from your life? Thoreau talks about a farmer who thinks he can’t live on vegetables alone because he needs a specific nutrient for his bones, so he toils away for this bone food. Meanwhile, another farmer in a different part of the world has never heard of this bone nutrient, yet his bones are just fine. There are so many things we think we have to do. But really, most things are inessential. We can cut them out altogether. Very little input is needed from us. Nature takes care of most things.

- Not wanting is the same as having; either way, anxiety is relieved.

- Willingness is the key. What good is it to have done something great but against your will? If you complained while doing it? This is how people tear themselves apart, Seneca said. The body goes one way, the mind another. To do something with reluctance is foolish. We must act on our toes, not our heels.

- Nature does the hard thing…and defends itself against all opposition to being spontaneously itself.

- Don’t settle for doing comparatively good things. Thoreau tells the story of the Englishman who traveled to India to make a fortune before returning to England to live the life of a poet. “He should have [become a poet] at once,” Thoreau said. “‘What!’ exclaim a million Irishmen starting up from all the shanties in the land, ‘is not this railroad which we have built a good thing?’ Yes, I answer, comparatively good, that is, you might have done worse; but I wish, as you are brothers of mine, that you could have spent your time better than digging in this dirt.”

- When you hear a piece of wisdom, don’t just think, “Oh, that’s great. Love it.” Spend time with it. Really think about how you can apply it to your own life. Then apply it.

- Wisdom means always wanting the same things and always rejecting the same things. If an action is consistent, you can be sure it’s right.

- Real dangers have inherent limits. Everything else is up to opinion and conjecture and, therefore, endless anxiety.

- The best work is the work that connects the human to the divine. William Blake believed he could help society most by using his imagination and creating his art. Elizabeth Gilbert said the best kind of life is one spent digging for buried treasures inside yourself. And it doesn’t matter if you’re paid for it. (In fact, it’s better that you’re not paid for it. That way, as Elizabeth Gilbert explained, you don’t put pressure on your creativity.) It’s so important to spend time each day doing work that is its own reward.

- Stop paying attention to other people’s curated lives. Your default response to most of the random information that bombards us every day should be holy shit I don’t care. Protect your time and attention more fiercely than your money and property.

- If you’re a parent, use your money to help your kids now. It’s not going to do them much good to give them an inheritance when they’re 60 and no longer need it.

- This is the #1 productivity/happiness rule I’ve found to be true: get up early. Give the first hour or two of the day to yourself. You can read or journal or go for a walk or sit and savor a cup of coffee or work on something you care about. (Just no getting on your phone!) The idea is to give the best part of the day, the morning, to yourself—before work, before your kids are yelling for you, before all the responsibilities of daily life demand your attention. It’s true: win the morning and you win the day.

- To that add: do the hardest work of the day in the morning. That way, the rest of the day is easy.

- Stop reading/watching the news. If you ask a good-humored, well-put-together person their secret, there is a zero percent chance they’ll say, “You know what’s really helped me be a better spouse? I watch a lot of news.” You can easily stay informed with a quick 3-minute weekly news scan.

- Our lifetime is short, a mere blip, the length of a pinprick. There are no vast amounts of time in our lives; how can there be a vast amount of basically nothing? Seneca asked. When we say something happened just now, that “just now” covers a fair portion of our lives, including the past, because our whole lives are so short. So we must be mindful of how we spend even “small” amounts of time—they account for much of our life!

- One of the problems with materialism is that too much attention on stuff dims the natural beauty of all around you. The people in your life are the brightest, shiniest things of all. Life, like a great story, is about people.

- It’s not intelligence but original thinking that will set you apart. Have some controversial ideas, too.

- Don’t think you need to read every book cover to cover. Something I want to do more of this coming year: more scanning, more diving in and out of books. Not letting a book sit endlessly on the shelf just because I think I have to read all of it.

- “The happy life is just one life,” Seneca said. It’s an error to compare your life to anyone else’s because your life is the only one you can possibly live. Another person’s life has no bearing on your happiness. If a person lives longer or bigger or more far-reaching, it does not follow that they live better. A life can be measured only by its own fullness. If you’re fulfilled, what does it matter how someone else is fulfilled? One eats less, the other more. What difference does it make? Both are filled.

- Diseases of the mind are the hardest to detect. The healthier we think our mind, the sicker it is.

- Value your time more than your income. Instead of trying to create more income, Thoreau built a small house in the woods and decided to create more time. Instead of seeing how much he could accumulate, he wanted to see how much he could do without. He found that by keeping his needs minimal, he could get by working just one day a week and take the other six off. Time is what makes a person happy, he said. Not fame or money. Time. Time for contemplation. Time for exploration. Time for your loved ones. Time for yourself. Time is happiness.

- Seeking praise will lead you astray.

- I recently heard a successful, near-retirement-age CEO of a midsize company say that if she were to sit down for breakfast in the morning with her husband and look at her calendar and have no meetings or business-related items on her to-do list for the day, that would be her biggest nightmare. And she was proud of it. I felt kind of bad for her. It made me think of what Josef Pieper said, that overwork can trick you into thinking you’re living a fulfilled life.

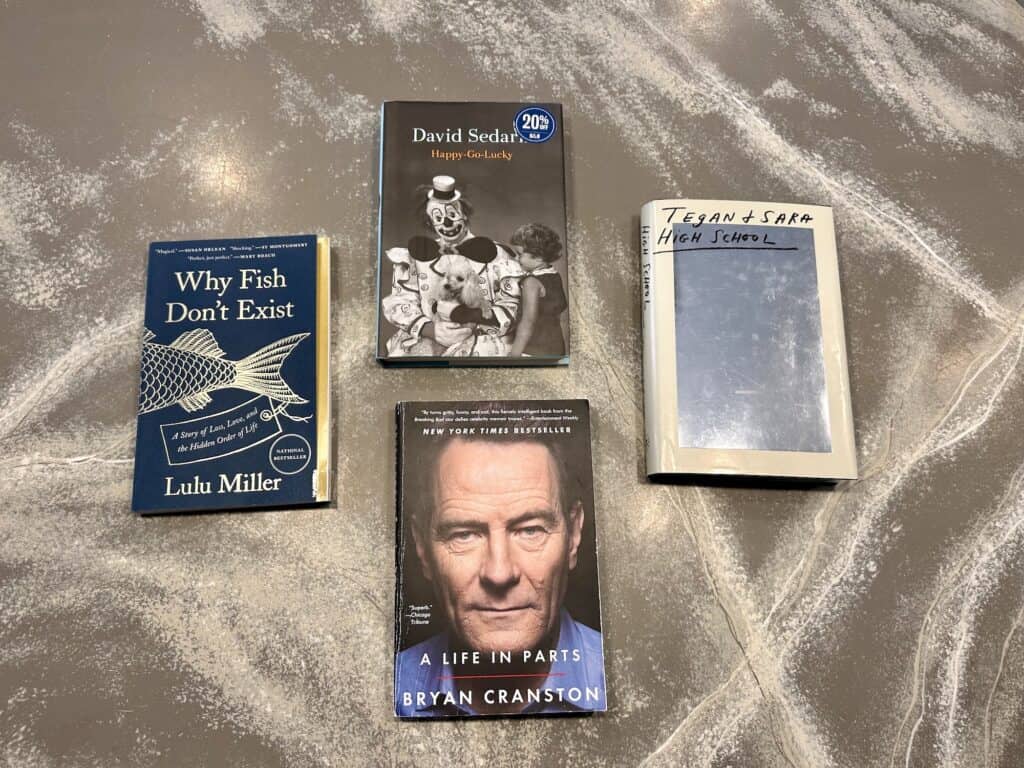

- You shouldn’t read books to impress people or as a way to escape. Reading should be for figuring things out, for understanding yourself and the world, for challenging yourself, and for learning from the experiences of others. (Here are some great recommendations!) A biography might take weeks to read, but the lessons you learn can save you decades of personal trial and error. That’s why even though it’s time-consuming, reading will always be the ultimate shortcut.

- The two tasks you have in life: be good and become more of yourself (by pursuing work you love).

- To create real change, you must learn how to attract and wield power.

- Done is better than good. Make stuff and put it out there. Who cares what other people think? Seriously, who cares? Stop worrying. As Marcus Aurelius said, ‘There’s no need to be anxious. Nature takes care of it all. Soon enough you’ll be dead, and the people who remember you will die too.’

- Trust yourself. It’s not that geniuses have all these great thoughts the rest of us don’t have, Alain de Botton said, it’s that they take them more seriously.

- Don’t be content with quoting others. You have to bring your own thoughts to the table.

- How much time do I waste entertaining every random thought that pops into my head?

- Better to waste money than time.

- You can’t just think your way into good ideas. You have to roll up your sleeves and do the work in front of you. Breakthroughs are often hidden in hard work.

- Serve the work. Don’t impose your will on it. Let it be what it wants to be.

- Mornings are great for idea-generating.

- In every moment, for every person, there is the opportunity for complete happiness because there is an opportunity to practice a virtue. In this way, happiness has a fixed limit. Once fulfilled, any additional pleasures can only slightly enhance it. In other words, there’s no need to take the long way; happiness is available right now, in the next reasoned action we take. It’s right in front of us. We just need to grab it.

- Who’s going to give you back your time?

- Important work—not urgent work—should make up the biggest portion of your day. Don’t get sucked into doing task after task after task. Too many urgent things on your to-do list might indicate a lack of planning.

- If everything you do is simply what you do, then there’s nothing to calculate and no reason to hesitate. There is no “being brave”; there is just being yourself. ‘That was a really brave thing for her to do.’ No, that was a really her thing for her to do. That’s what she does. She moves from one necessary activity to the next and regards the outcome as irrelevant.

- Grateful is the best state of being. It is divine. At the end of my life, I hope to leave grateful and without complaint, as Marcus Aurelius said, “like an olive that ripens and falls. Praising its mother, thanking the tree it grew on.”

- Don’t be satisfied with doing work that gets you by. Find work to be invested in. You get one life. Why would you spend it doing things you don’t care about? I love how Elizabeth Gilbert put it: “What else are you going to do with your time here on earth—not make things? Not do interesting stuff? Not follow your love and your curiosity?”

- A great way to live: follow your interests and share them with the world.

- And finally, one of my favorites: We can’t always be calm. But we can make an effort to be calmer than we were last year.

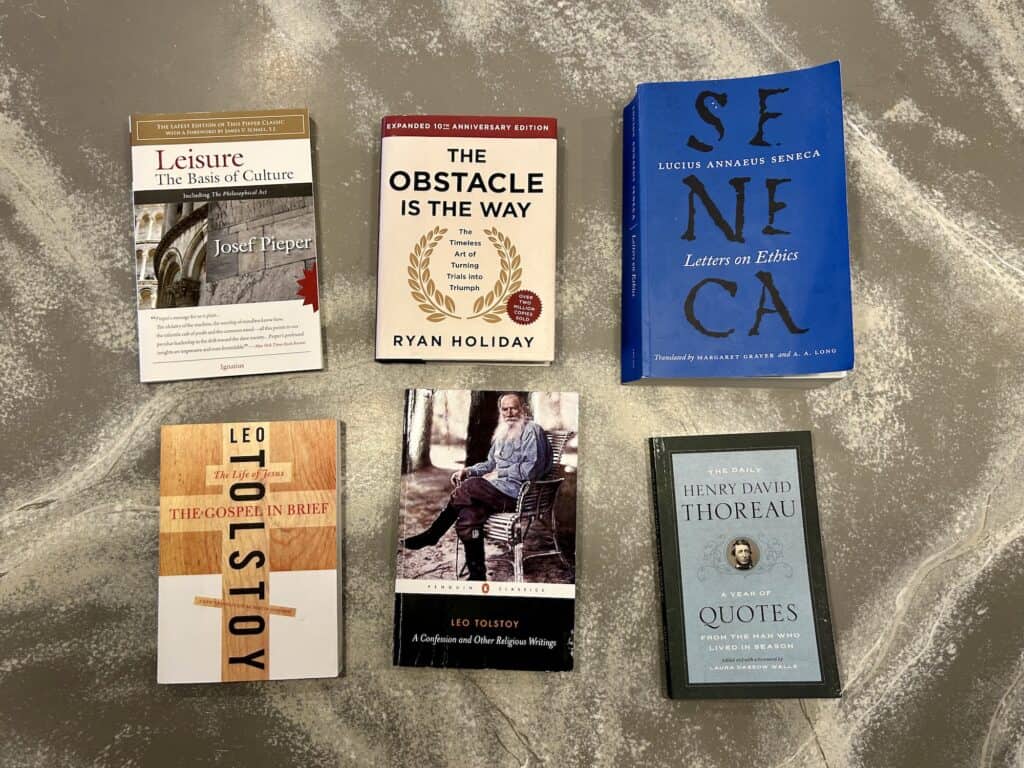

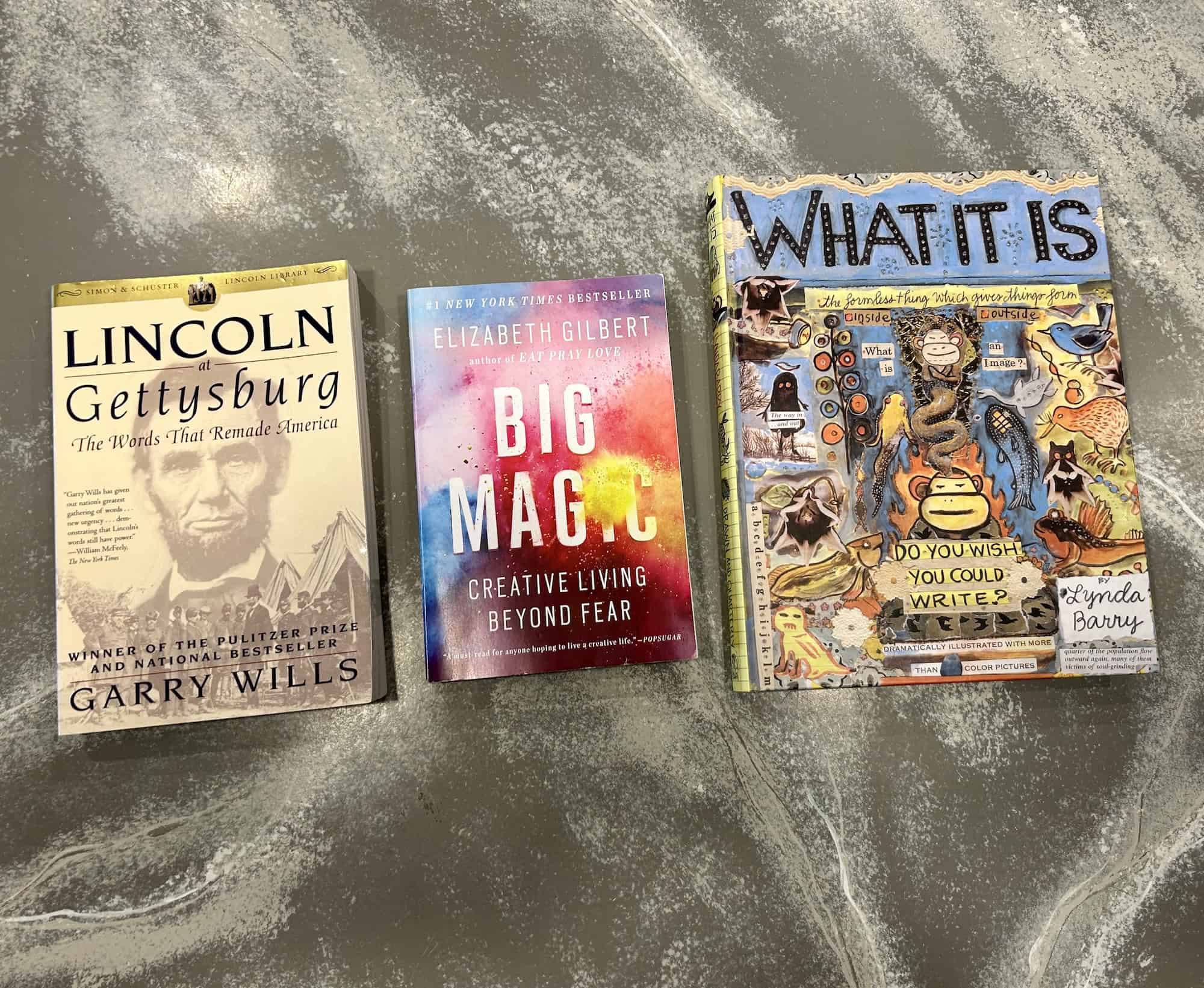

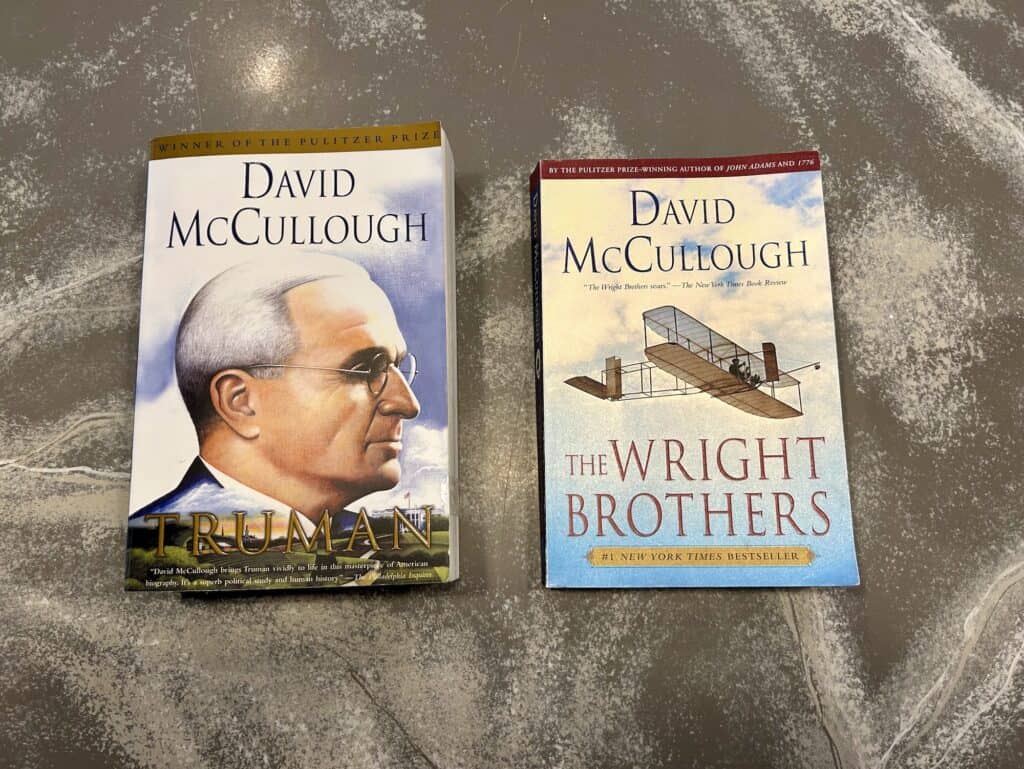

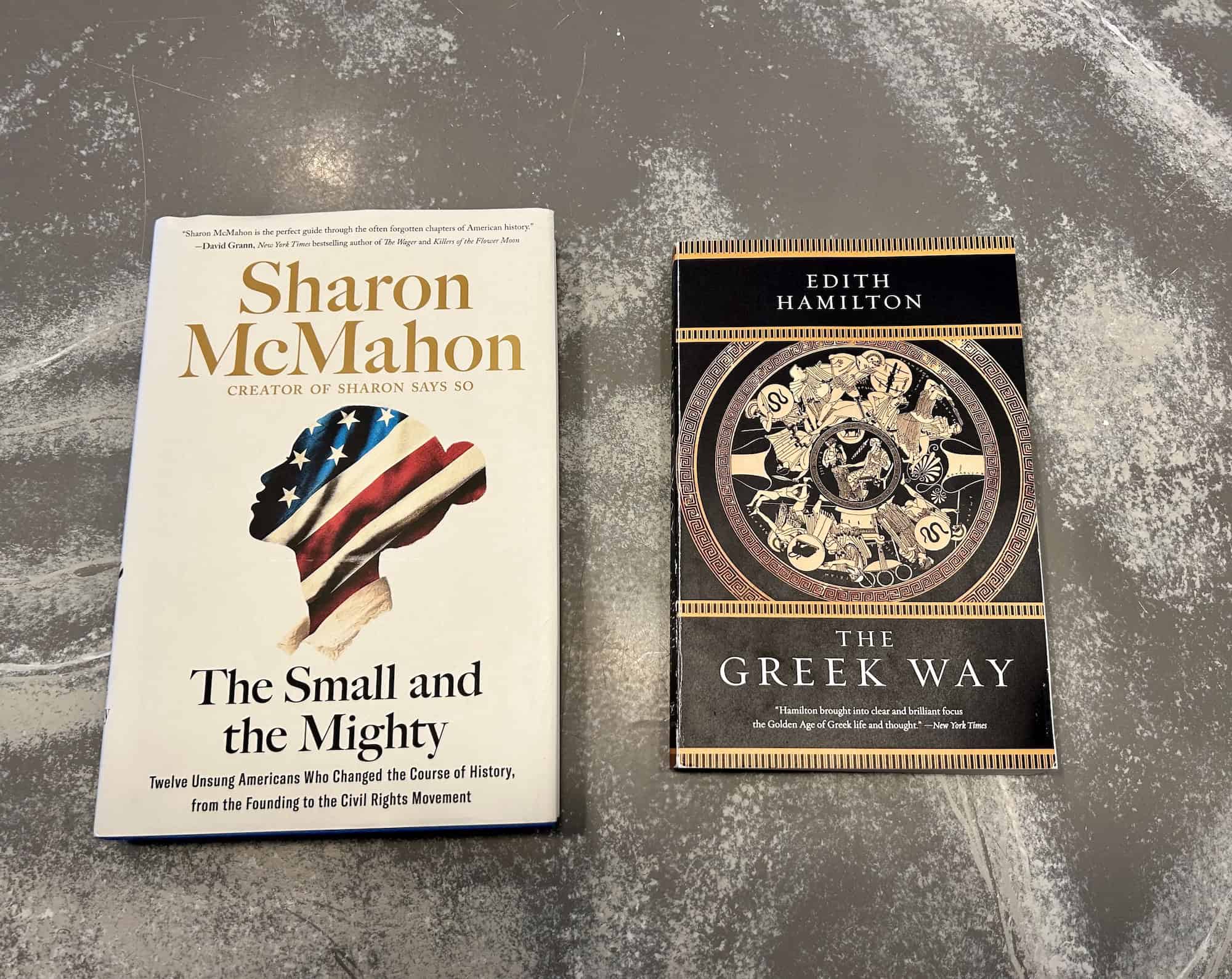

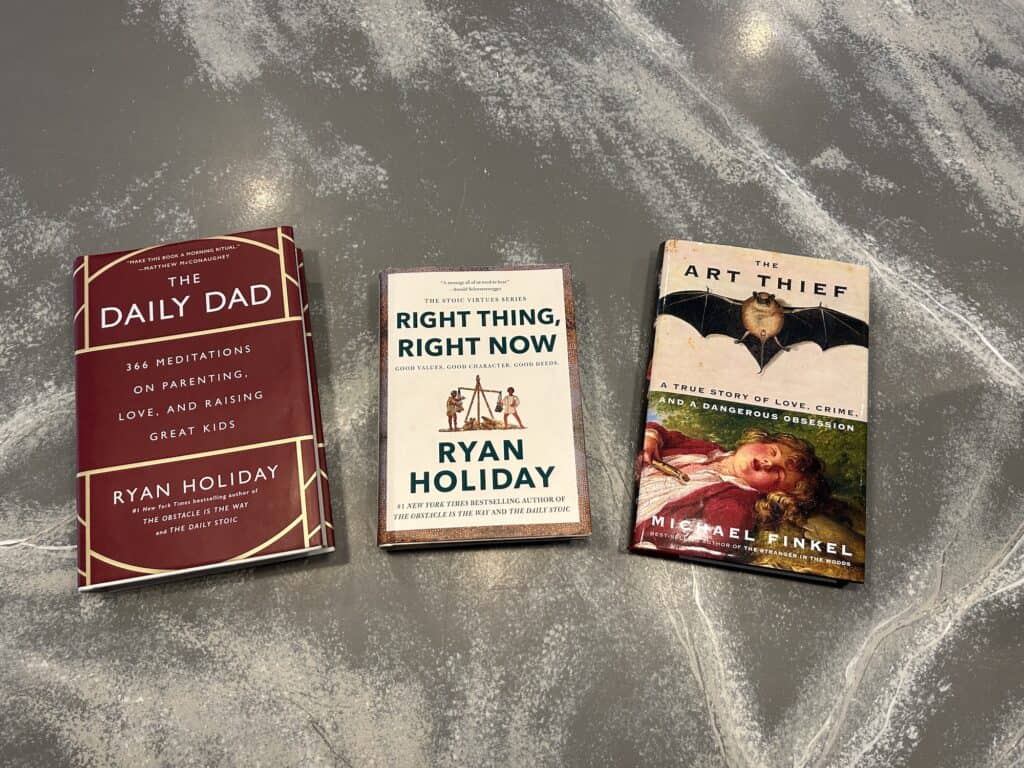

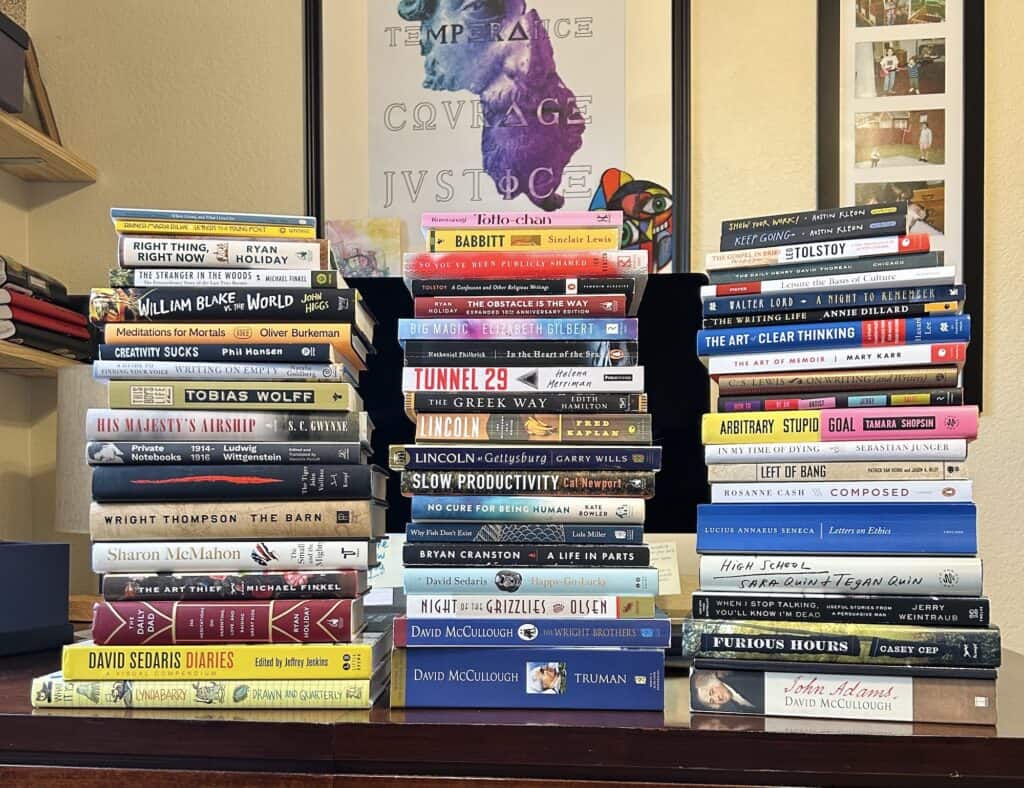

Books Read This Month:

–The Small and the Mighty by Sharon McMahon was one of the best of the best books I read this year. It’s full of mini-biographies of real people who were powerless by society’s standards but created their own power through creativity, daring, and perseverance. These lesser-known but arguably most important characters of history accomplished more than probably what even they thought was possible. It’s hard to read this book and not be inspired. It’s seriously so good.

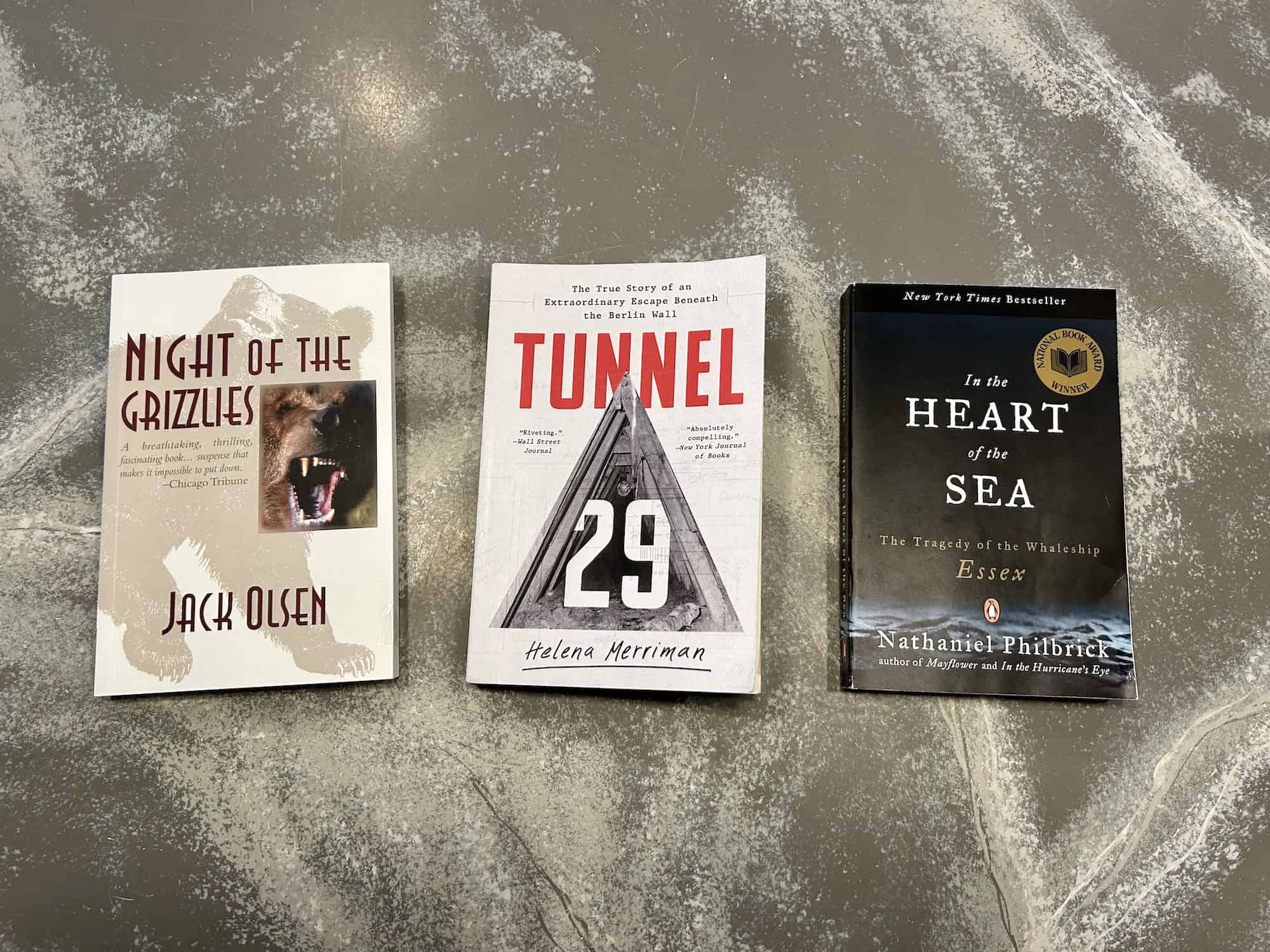

-Oh my goodness, The Night of the Grizzlies by Jack Olsen is SO good. In 1967, Montana’s Glacier Park allowed campers to feed the grizzly bears. After dinner, they would throw table scraps down from the lodge and onto the campgrounds to watch the grizzlies dine. Warnings are ignored, and the suspense ratchets up because we know what’s going to happen: two nineteen-year-old women are killed on the same night by two different grizzlies in two separate locations.

-I loved Lincoln: The Biography of a Writer by Fred Kaplan. It’s a biography of Lincoln in the context of the books he read and how they shaped his thinking and writing. Lincoln believed the written word to be humanity’s most important invention—an invention he used to create his most famous speech and forever shape how we view America…

–Lincoln at Gettysburg by Garry Wills is another one of the best books I read this year. Lincoln was a master of persuasion. Today’s politicians speak in polarizing, black-and-white, us vs. them terms, so it was especially refreshing to read Lincoln’s speeches. Any crowd he spoke to, he always found the common ground, the ‘Hey, I want what you want’ approach. And this approach wasn’t a ploy—he did want what they wanted because he knew that all people mostly want the same things; all the rest was rhetoric. He instinctively knew how to speak to people on both sides. Just a master communicator. And what I learned has helped me tremendously in my own conversations with people. I marked and dog-eared almost every page.

–I got some great stuff from Cal Newport’s book on productivity without burnout. Slow Productivity consists of three things: do less, work at a natural pace, and obsess over quality.