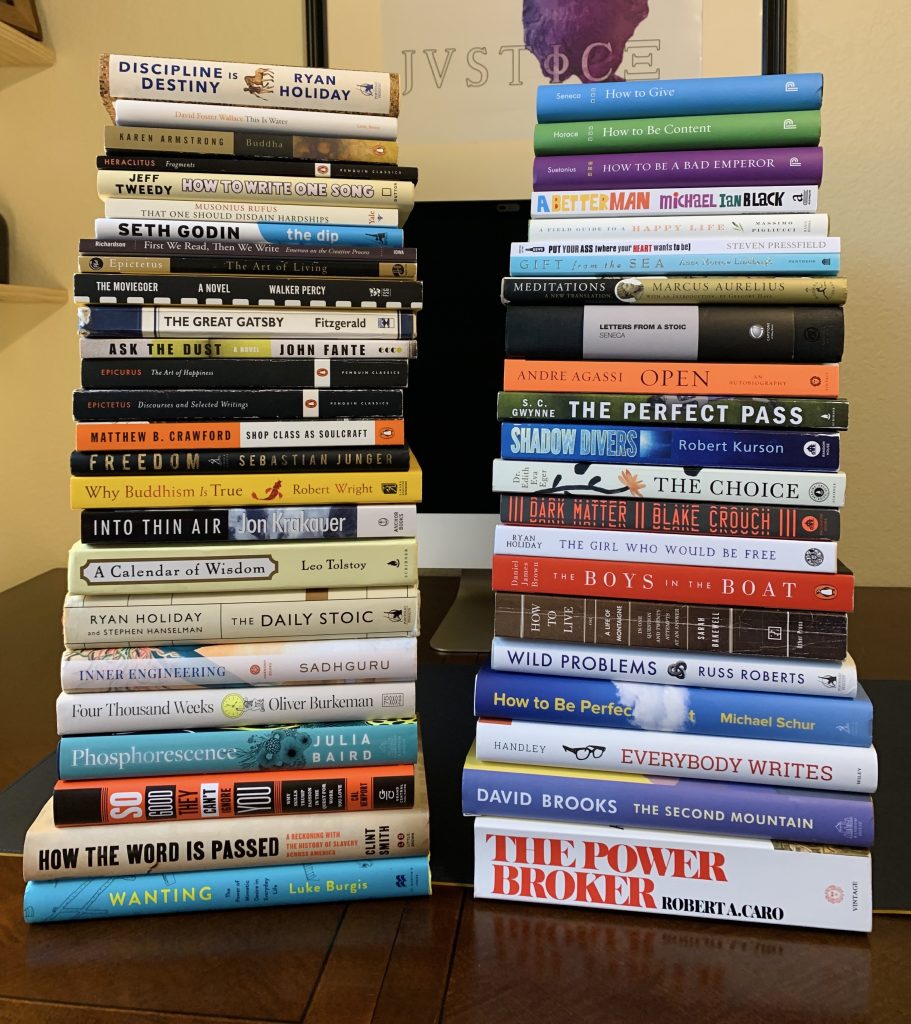

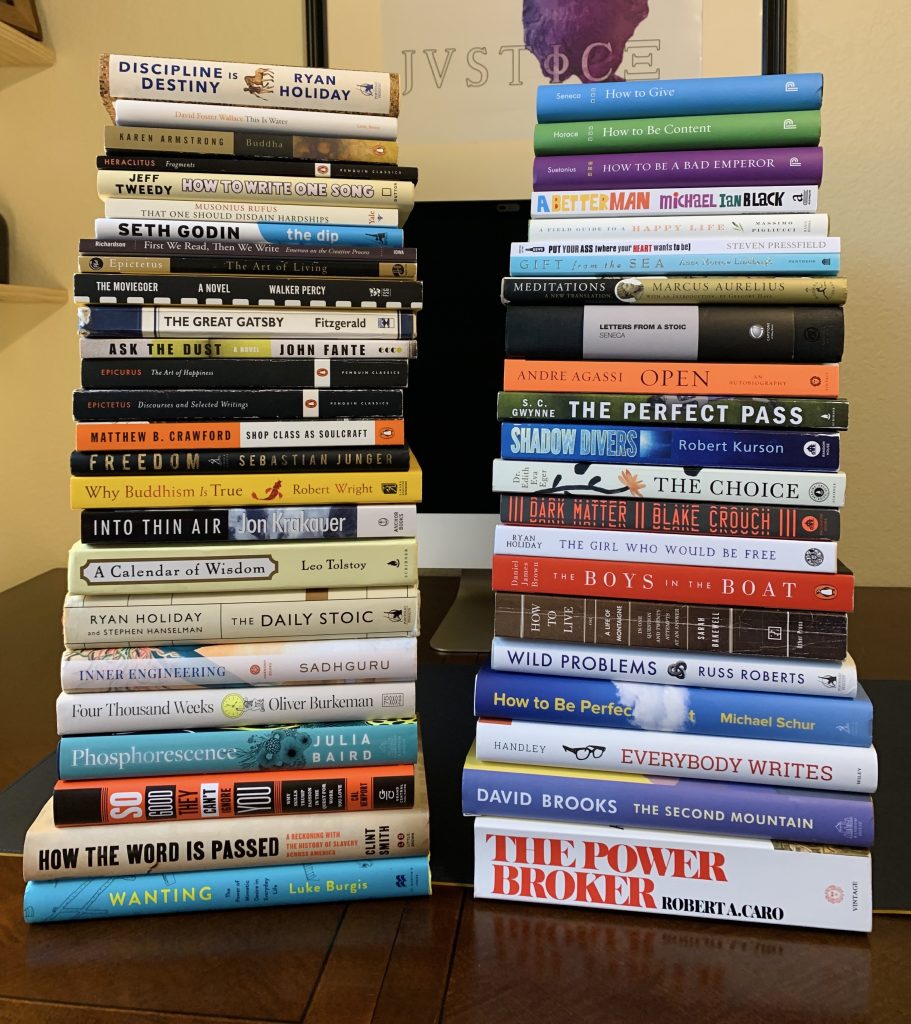

Books read in 2022

I found so many gems in the books I read this year and, as I did last year, put together a list of one takeaway from each. Enjoy!

I found so many gems in the books I read this year and, as I did last year, put together a list of one takeaway from each. Enjoy!

It’s surprising how much you can read in a year when you read a little bit every day. I read ~50 books this year and I still feel like I could have been more disciplined about it. Good books have changed my life, and reading them helps me be a better person. Below are the best books I read this year. And I recommend you read them as well!

Buddha by Karen Armstrong

This is a wonderful, readable biography of the Buddha. We tend to think of enlightenment as the final destination. (What’s left to accomplish after reaching nirvana?) Maybe the Buddha believed this as well. But when he reached enlightenment, his sense of self disappeared. He saw at once the connectedness of all living things, and realized that “to live morally was to live for others.” It wasn’t enough that he reached nirvana—he had to help others reach it as well. He spent the next 45 years traversing the Ganges plain, spreading his dhamma to any and everyone he came across. His teachings survive today thanks to this “compassionate offensive”.

Discipline is Destiny by Ryan Holiday

No author has inspired or taught me more about life and philosophy than Ryan Holiday. This book on temperance (moderation) is the second in his four-part cardinal virtues series. He tells inspiring stories of people like Queen Elizabeth, Lou Gehrig, and Winston Churchill to illustrate the beauty of temperance, and contrasts it with cautionary stories of people like Alexander the Great and King George IV, who lacked temperance. I guarantee you’ll find something in this book that will enhance your life. Same with all of his books. This is one of my favorites of his, along with Ego is the Enemy, The Obstacle is the Way, and The Daily Stoic.

The Choice: Embrace the Possible by Dr. Edith Eva Eger

This book is just amazing. I gifted it to 2 friends and they couldn’t stop raving about it. Holocaust survivor Dr. Edith Eva Eger recounts the horrors of watching her parents be marched to the gas chamber, how she talked to herself through the unbearable realities of her imprisonment—“If I survive today,” she repeated to herself, “tomorrow I’ll be free.”—and how she ended up thriving in spite of it. Now a world-renowned psychologist, she gives her patients the advice that she learned long ago: the key to happiness and freedom is already within you. Life always gives you a choice. And as long as you have a choice, you’re free.

Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals by Oliver Burkeman

The average human lifespan is about four thousand weeks. Because of this “insultingly short” period of time, Burkeman says we have to neglect almost everything to get anything done. Good time management, therefore, is basically knowing what to neglect. Burkeman gives us practical philosophy about the best ways to spend our time, and therefore, our life.

How to Write One Song by Jeff Tweedy

This is a fun little book on creativity that Amazon recommended. As the title implies, it’s mostly about songwriting, but I found a bunch of useful gems on creativity. Tweedy starts the book with a story of himself at 7 years old, telling people he’s a songwriter. Not that he was going to be one when he grew up, but that he already was one. Never mind he’d never written a song. This idea of becoming who you already are, as opposed to molding yourself into a vision you have, is something I plan on writing more about.

Other great reads this year:

Why Buddhism is True by Robert Wright

Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life by Luke Burgis

Open by Andre Agassi

How to be Content by Horace

The Art of Living: The Classical Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness by Sharon Lebell

How to Be Perfect by Michael Schur

That One Should Disdain Hardships by Musonius Rufus

Inner Engineering: A Yogi’s Guide to Joy by Sadhguru

Put Your Ass Where Your Heart Wants To Be by Steven Pressfield

Discourses by Epictetus

How to Live: Or a Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer by Sarah Bakewell

The Art of Happiness by Epicurus

The Perfect Pass by S.C. Gwynne

The Boys in the Boat by Daniel James Brown

The Power Broker by Robert A. Caro

Wild Problems by Russ Roberts

Gift from the Sea by Anne Morrow Lindbergh

Letters from a Stoic by Seneca

Shop Class as Soulcraft by Matthew B. Crawford

And my all-time favorite books I read yearly:

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday and Stephen Hanselman

A Calendar of Wisdom by Leo Tolstoy

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

This year I tried to be extra mindful of how I spent my time. The Stoics said if you don’t want to waste your time, don’t focus on things that aren’t in your control. So I stopped looking at crypto updates. I stopped (or was at least mindful of stopping once I started) trying to figure people out. I stopped paying attention to the news. And I stopped being so tight-fisted with services that save me time (I had groceries delivered, hired professionals instead of doing it myself, etc.)

The result was that I got a lot done and had tons of free time. I spent every evening this year with my wife, saw my parents nearly every week, ran ~550 miles, read tons of great books, and started a newsletter.

The ideas I learned and used this year helped me so much, so I put together a list of the best ones. Below are the 22 ideas that helped me most in 2022. Enjoy.

1. The first rule for everything: don’t stress.

2. Focus on insignificant things, get insignificant results. Instead of tracking how many days you made your bed, track how many hours you spent reading a good book. Instead of a house-cleaning schedule, make an exercise one.

3. Habits are only habits if they’re done daily. Habits done once a week are obligations.

4. John Steinbeck said overwork is the falsest of economies. When you work, work hard. When you’re done, be done.

5. Clear the mental and physical clutter. I taped this quote from Discipline is Destiny to my computer: “A person who doesn’t eliminate noise will miss the message from the muses.”

6. Be ruthless about what you give your attention to. If an email is not addressed to you specifically, or if it starts with “Please Read…”, you probably don’t even need to open it. Open a book or a journal for a few minutes instead.

7. It’s better to read books that will enrich your life, rather than your career.

8. In order to have 1 good idea, you need to consume 10.

9. If someone tells you a book has changed their life, read it.

10. Everyone is doing their best with what they’ve been given. Socrates said that no one does wrong on purpose. The logic, of course, is that people who do wrong are harming themselves, and since people don’t harm themselves on purpose, they don’t do wrong on purpose. I really liked how Ryan Holiday wrote about it: People are doing the best they can with what they’ve been given. They weren’t given your brain, your experiences, your circumstances, your influences. The friend who repeatedly makes destructive choices, the sister who just can’t seem to get it together—surely they wouldn’t act this way if they knew the harm they were causing themselves. They wouldn’t act this way if they could help it. They’re doing their best, as we all are. If they’re open to advice, give it. If they’re not, let them be. Focus on the good in them. There are things that they’re better at than you. Learn from them. Most of all, love them. And be grateful with all your heart for the opportunity to share this beautiful, brief existence with them.

11. The higher tempo wins. If everything feels under control, you’re not going fast enough.

12. No two people can read the same book, see the same sunrise, or watch the same movie and get the same thing from it. Basically, nothing has been explored until it has been explored by you. Only you can find the treasures that will help you with your magnificent task or weird little thing.

13. There are fools and there are seekers of wisdom. Everyone else suffers. As Sadhguru put it in Inner Engineering, “An idiot is incapable of drawing conclusions. A [wise person] is unwilling to draw conclusions. The rest have glorified their conclusions as knowledge. The fool just enjoys whatever little he knows and [the wise person] enjoys it absolutely. The rest are the ones who constantly struggle and suffer.”

14. Only by being present can we live life to the fullest. As Oliver Burkeman put it in Four Thousand Weeks, a great experience “can still end up feeling fairly meaningless if you’re incapable of directing some of your attention as you’d like. After all, to have any meaningful experience, you must be able to focus on it, at least a bit. Otherwise, are you really having it at all? Can you have an experience you don’t experience? The finest meal at a Michelin-starred restaurant might as well be a plate of instant noodles if your mind is elsewhere; and a friendship to which you never actually give a moment’s thought is a friendship in name only.”

15. Let it float on by. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about discarding thoughts: if a toxic thought pops into my head, I can immediately discard it. When I told my wife about this, she pointed out that in order to discard something, I first had to possess it. It’s better, she said, to watch the thought from a distance, and let it float on by.

16. Don’t let anyone tell you reading isn’t work. I schedule a half hour each day to read (instead of just reading when I have time) and try not to miss it. Reading is hard work. And it’s some of the most important work you can do.

17. Reflective thoughts are truer than everyday thoughts. As we go about our day, thoughts pop into our heads seemingly out of nowhere. These thoughts can be irrational or impulsive, which can lead to feelings that are irrational or impulsive, which can lead to actions that are irrational or impulsive. That’s why reflection is so important. It’s why journaling or meditating or taking 5 minutes to ourselves is so important. So we can slow down. So we can be present. So we can take our brains off autopilot and hear the whispers of our hearts. So we can stay in touch with ourselves. As Anne Morrow Lindbergh said in her beautiful book Gift from the Sea, “If one is out of touch with oneself, then one cannot touch others.”

18. Only fools constantly regret their actions.

19. Seneca said if we’re not grateful right now, we will never be grateful, even if we’re given the whole world.

21. Slow productivity. Do fewer things, work at a natural pace, and obsess over quality. And if you’re a creator, focus on what does not yet exist.

22. Many mickles make a muckle. Keep going, even if it doesn’t seem like you’re making progress. You are. It’s slowly adding up. The interest is compounding. Keep going.

We feel lousy when we think other people are doing better than us. We feel superior when we think we are doing better than other people. Basically, as Ryan Holiday put it, there are only two ways that comparing yourself to others can make you feel: crappy or egotistical.

Comparing ourselves to others is the gateway to competing with them. And if we’re not careful, we end up competing for the sake of competing. Instead of a means to an end, it becomes an end in itself. We end up playing a game we don’t actually care about—and dulling our shine to stay in it.

Lamborghini’s Refusal To Compete

Before becoming one of the world’s best carmakers, mechanic Ferruccio Lamborghini built tractors. He also drove and modified Ferraris. Souping up his red Ferrari 250 GTE Pinin Farina Coupe, he would speed past the best drivers in the world—Ferrari test drivers—and leave them in disbelief. But, as Luke Burgis writes in Wanting, Lamborghini had been having mechanical problems with his Ferrari. One of those problems was the clutch. It didn’t feel right. Upon inspection, he realized the clutch in his $87,000 luxury car was the same clutch he used in his $650 tractors. When he brought this to the attention of Ferrari founder, Enzo Ferrari, he would hear nothing of it. So, Lamborghini decided he would make his own luxury car.

He founded Automobili Lamborghini in 1963 and made his first car in 1964. Four years later, in 1968, he released the Miura P400s—an iconic car that both Frank Sinatra and Miles Davis bought. With the success of the Miura, Lamborghini’s engineers pleaded with him to make a car that could hold its own in a race against a Ferrari. But Lamborghini refused. While he knew that, to a point, competition could be good (after all, Lamborghini used Ferrari’s inadequate clutch as fuel to start his own company), he also knew the dangers of rivalries and how quickly competition could devolve into one. So he didn’t give in. (Future leaders of Automobili Lamborghini were eventually lured into the race car business, but not while Lamborghini was still alive and running things.) Rivalries, he knew, had no end. Lamborghini invested his energy into opportunities and craftsmanship. The result was that he built not only a successful business but also, on his property, a barn that he filled with his favorite models of Lamborghini automobiles. And he was able to spend the last twenty years of his life in peace, giving fun tours of his favorite cars to visitors.

How To Have a Good Shot at Building the Best

Builder of the world’s best racing shells for crew teams, George Pocock was “all but born with an oar in his hand.” Both his paternal and maternal grandfathers were competitive boatbuilders. His father built competitive racing shells for Eton College. George followed in his family’s footsteps by combining his boat knowledge with his peerless love of craftsmanship. At the height of his career, he was building and supplying racing shells to almost every top crew university in the country (including Washington University, whose crew team won a stunning victory at the 1936 Berlin Olympics). His racing shells were superior to others. Each shell was built with care and patience—possibly because of the advice his father had given him when he was younger: “No one will ask you how long it took to build; they will only ask who built it.”

Pocock, like Lamborghini, would not compromise his craftsmanship for competition. When a crew coach all but demanded Pocock reduce his $1,150 per-shell price, arguing that other racing shells weren’t nearly as expensive, Pocock wouldn’t budge. He flatly refused to lower his price to compete with other suppliers. “I cannot build all of them,” he said, “but I can still have a good shot at building the best.”

Pocock, like Lamborghini, would not compromise his craftsmanship for competition. When a crew coach all but demanded Pocock reduce his $1,150 per-shell price, arguing that other racing shells weren’t nearly as expensive, Pocock wouldn’t budge. He flatly refused to lower his price to compete with other suppliers. “I cannot build all of them,” he said, “but I can still have a good shot at building the best.”

False Desires are Limitless

Seneca said that natural desires are limited, but false ones are limitless. Vanity, pleasure-seeking, rivalries—all these are limitless. How, then, are nature’s desires satisfied? By sticking to your own reasoned principles. “When you would know whether that which you seek is based upon a natural or upon a misleading desire, consider whether it can stop at any definite point,” Seneca said. “If you find, after having traveled far, that there is a more distant goal always in view, you may be sure that this condition is contrary to nature.”

One of my favorite reads this year has been Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks. And I’ve thought a lot about this passage:

“The only definitive measure of what it means to have used your weeks well: Not how many people you helped, or how much you got done; but that working within the limits of your moment in history, and your finite time and talents, you actually got to doing—and made life more luminous for the rest of us by doing—whatever magnificent task or weird little thing it was that you came here for.”

Isn’t that beautiful? For some reason, it reminded me of a couple of stories in Shoe Dog, another book I love.

Jeff Johnson’s Thing

Before Nike founder Phil Knight hired Jeff Johnson as Nike’s first full-time employee, Johnson worked as a social worker for Los Angeles County. On the weekends he sold Tigers—the Japanese running shoe made by Onitsuka. Johnson loved running and had a romantic view of it. It was almost like a religion to him. He believed that, done right, runners could run themselves into a spiritual, meditative state. One day in April 1965, his supervisor said that he didn’t think Johnson cared about his job as a county social worker. Johnson realized he was right—he didn’t care. So he quit. That day he realized his destiny—and it wasn’t social work. His destiny was to help runners reach their nirvana. “He wasn’t put here on this earth to fix people’s problems,” said Knight. “He preferred to focus on their feet.”

Belief

Before founding Nike, Knight was a salesman—a terrible one. Selling encyclopedias door to door had been a bust. He was only slightly more successful selling mutual funds. He resigned himself to the idea that he just wasn’t a salesman. But when Knight, a lifelong runner, received his first big delivery of Tigers (he had worked out a deal with Onitsuka who was seeking expansion in America), things changed. With a trunk full of Tigers, he drove around to different track events and showed them off to players, coaches, and spectators. He couldn’t write orders fast enough.

He wondered why he was able to sell shoes but not encyclopedias. Was the difference in his selling ability really a matter of product? Then he realized: it wasn’t a matter of selling at all. It was a matter of belief. He believed in running. He believed the world would be a better place if people ran a few miles every day, and he believed that the shoes he was selling were better to run in. “People, sensing my belief, wanted some belief for themselves,” he said. “Belief, I decided. Belief is irresistible.”

Stay the Course

Seneca used the Greek word euthymia for “believing in yourself and trusting you are on the right path, and not being in doubt by following the myriad footpaths of those wandering in every direction.” He said we should make this a constant reminder—to stay the course and not give in to distraction. Marcus Aurelius reminded himself to stay focused on doing his duty. “Concentrate every minute like a Roman . . . . on doing what’s in front of you with precise and genuine seriousness, tenderly, willingly, with justice.” With justice. With what’s fair, what’s right, and what’s useful for the common good.

Just that we do our duty, our magnificent task or weird little thing, and that we do it with justice, to make life more luminous for others.

These are two metrics that can guide us each day, and always.