If we can’t be present now, we can’t be present later

This month, Courtney and I drove from Phoenix to San Diego for a bridal shower and mini vacation. The drive is ~5 hours and relatively easy, minus the winding mountain roads during the final stretch (at which point you can just let your California native wife take over, and close your eyes as she whips the car around 90-degree turns, at elevations of 4,000 feet, believing any consideration of physics and its laws to be an excuse used by slow, bad drivers).

As usual on road trips, I was counting down the minutes until our arrival, excited about everything we would do. But as I sat behind the wheel, cruise control on, an open road ahead, listening to one of my favorite books with my wife, I wondered why I was in such a hurry to get there.

It’s something I never thought much about, it’s just what you do—get there as fast as possible. When you’re a kid you whine, are we there yet? When you’re an adult you already know you’re not there yet and you won’t be there for another 256 miles. Traveling is the inconvenient part of vacationing, the part you muscle through to get to where you want to be.

But as Interstate 8 stretched on, I thought about what a great time I was having. Why am I rushing through a beautiful drive with my best friend? So I can get to the hotel sooner? So we can check in and head to the beach? So we can sit and enjoy each other’s company and do essentially the same thing we are already doing?

I realized I was already having the time of my life! What I wanted wasn’t over there, it was right here, just waiting for me to notice.

It struck me how absurd it was to think I could be present at the beach when I couldn’t even be present in the car. It reminded me…

If We Can’t Live In This Moment, We Can’t Live In Any Moment

When Thich Nhat Hanh would have friends over for dinner, he had a routine of washing the dishes afterward before sitting down to drink tea with everyone. One evening, his friend Jim Forest asked if he may wash the dishes. Go ahead, Thich replied, just remember there are 2 ways to wash the dishes: “The first is to wash the dishes in order to have clean dishes and the second is to wash the dishes in order to wash the dishes.” If we’re washing the dishes to get to the tea, we aren’t really washing the dishes. The rest of Thich Nhat Hanh’s assertion is worth quoting in full:

“What’s more, we are not alive during the time we are washing the dishes. In fact, we are completely incapable of realizing the miracle of life while standing at the sink. If we can’t wash the dishes, then chances are we won’t be able to drink our tea either. While drinking the cup of tea, we will only be thinking of other things, barely aware of the cup in our hands. Thus we are sucked away into the future—and we are incapable of actually living one minute of life.”

You’re Exactly Where You’re Supposed to Be. Enjoy It

In Ethan Hawke’s beautiful book Rules for a Knight the protagonist, Sir Thomas Lemuel Hawke, recounts a time in his childhood when he went to see his grandfather to ask him for advice about how to live his life. His grandfather welcomed him warmly, happy to share his wisdom. The boy congratulated himself for coming, saying, “I knew I’d come to the right place.” His grandfather looked at him and said, “I’m glad you’ve come, Thomas. I’ve been hoping you’d show your face at my door for a long time, and I will happily accept you as my squire, if that’s what you want. But the first thing you must understand is that you need not have gone anywhere. You are always in the right place at exactly the right time, and you always have been.” He then paused and asked the boy, “Do you know why King Arthur’s knights could not see the mountain peak of Sea Fell?” Thomas said he did not. “Because,” his grandfather smiled, “that’s where they were standing.”

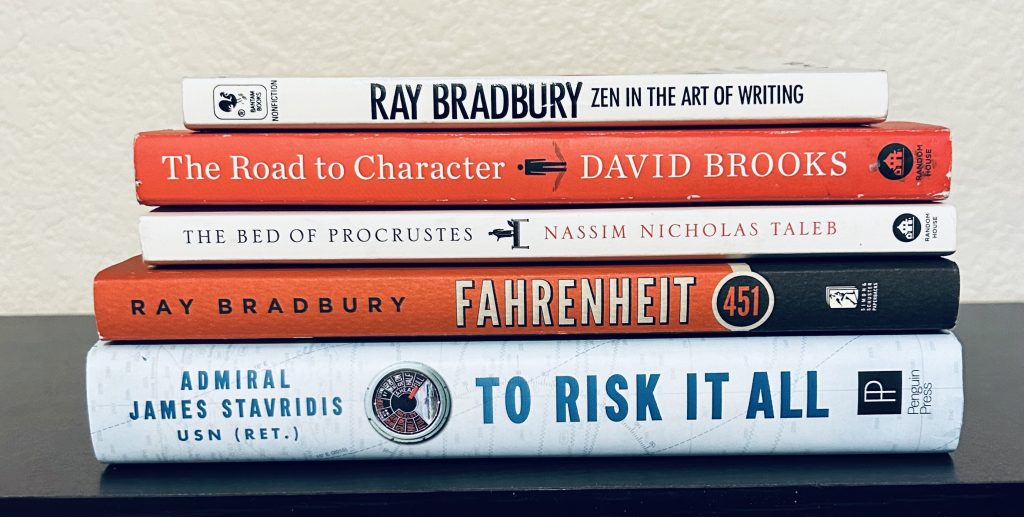

Books Read This Month

The Consolations of Philosophy by Alain De Botton is amazing. Each chapter comprises 2 things: a common, specific problem and a posthumous philosopher with the best solutions for it. From how Socrates dealt with unpopularity (and why it’s sometimes a good thing to be unpopular), to how Montaigne overcame his perceived inadequacies, it gives an abundance of excellent advice. It’s one of the best books I’ve read this year. I read You Are a Writer (So Start Acting Like One) and Real Artists Don’t Starve by Jeff Goins. I added both to my list of favorite books on writing and creativity, and both helped me understand that as much as art needs business, business needs art, and to not sell yourself short. I read Lord of the Flies by William Golding for the first time which was, of course, great. We listened to one of my favorite books, The Obstacle is the Way, by Ryan Holiday on our road trip. I read Ethan Hawke’s wonderful, philosophical gem Rules for a Knight and I loved it. I also read James Romm’s Dying Every Day, an awesome biography of Seneca during his time as an advisor to the unhinged Nero. It’s a great mix of drama, history, and philosophy.