12 more things I learned or found useful in 2023

1. We don’t need more time, we need more focus. We all have the same, fixed amount of time in a day. But with a little mindfulness, we can expand our time. Think about all the things you can do in 15 minutes. You can read a few pages of a book. You can call your mom. You can help your spouse prepare dinner. Now think about all the ways 15 minutes can slip by without notice. Scrolling through newsfeeds, small talk, zoning out in front of the TV. Seneca put it best when he said that time doesn’t slow down to let us know it’s passing by. It’s our responsibility to mind it. We can’t create more time, but we can put the time we do have to good use.

2. The best way to show someone respect is by doing your best.

3. Donald Miller said, “A good movie has memorable scenes and so does a good life.” I’ve been thinking about this lately, especially when I’m out with family and friends. What’s a little extra something we could do to make this more memorable?

4. Don’t let your days become one chore after another. Life requires balance. And space.

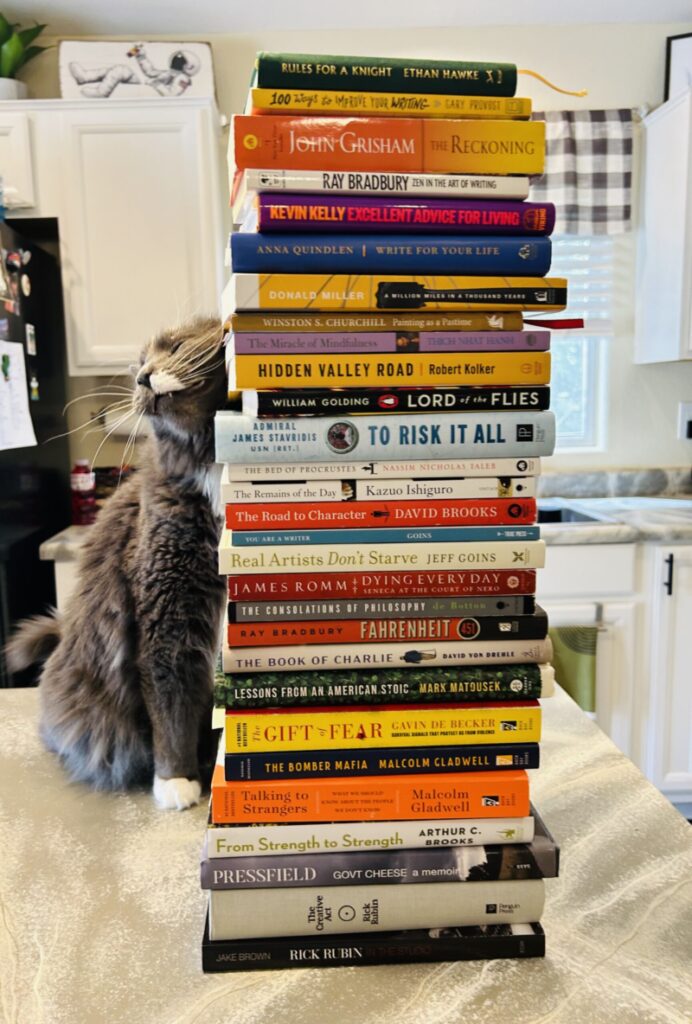

5. Setting time limits can relieve stress. For almost a decade, I’ve had the same system for notating the books I read. After I finish a book, I put it in a “to-notate” pile. Later, with notecards and pen in hand, I systematically go back through them and jot down the parts I marked. Recently, I was overwhelmed by the ever-growing stack of books in the “to-notate” pile. This was supposed to be fun, not stressful! So, I decided to impose a time limit. I don’t allow myself to take notes for more than 2 hours a week (or roughly 10-20 minutes per day). Putting this limit on myself made the process fun again and allowed me to enjoy my free time more. Plus, the time limit forces me to write down only the best stuff from each book. Then, on to the next.

6. Getting up early is the key ingredient to living a better life. Ernest Dimnet said, “An hour in the morning is worth two.” I’ve thought about that for years now, and it’s true.

7. I’m always thinking about how short life is. Or rather, I’m highly mindful of how I spend my time. Or, perhaps more precisely, you could say I’m obsessed with weeding out the inessential from my life. (Sometimes to a fault). Why would I accept a promotion if it meant less time with my wife? Why would I allow my schedule to be too packed to see my parents every week and help them when they need it? Why would I spend an hour at the grocery store when I can spend an hour outside playing with my dog and have the groceries delivered? Why would I go to a gym when I have the equipment at home? I can imagine someone reading this and thinking, gee whiz, just live your life. But to me, this is living my life! Hanging out with my wife, helping my parents, playing with my dog, creating space for spontaneity—that’s the stuff that makes life worth living (and makes me the luckiest person)! That’s how I want to live my life, surrounded by what’s most important. The 2 quotes I read this year that have really shaped my thinking on this:

Epictetus: “If we keep in mind constantly how short our life is, we will realize there is no room for excess.”

Seneca: “We don’t have enough time for what’s necessary, let alone what’s unnecessary.”

8. What if we replaced the word envy with admire? We can be quick to shut down thoughts of envy. But, Alain de Botton says, if we take a moment to explore this feeling, we may find what lies beneath is not envy, but admiration. And we usually don’t envy someone’s entire life. Usually, it’s just a part that we envy (admire). And once you’re clear about what you admire, you can work to incorporate it into your own life. Let’s say you envy a successful entrepreneur’s life. You dig a little deeper and realize you don’t actually envy her life—it’s too hectic. What you envy, or admire, is her flexible schedule. Knowing precisely what it is you admire—her autonomy—gives you a clearer vision of what you’d like in your own life. You can then take steps and, say, make a career change to have more flexible work hours. You can repeat this process on multiple people, taking bits and pieces you admire, and fitting them together to create your ideal life.

9. With anything you endeavor to do, the whole point is to have fun. Do the things that you find most interesting.

10. Richard Feynman on happiness: “My rule is when you are unhappy, think about it. But when you’re happy, don’t. Why spoil it? You’re probably happy for some ridiculous reason and you’d just spoil it to know it.”

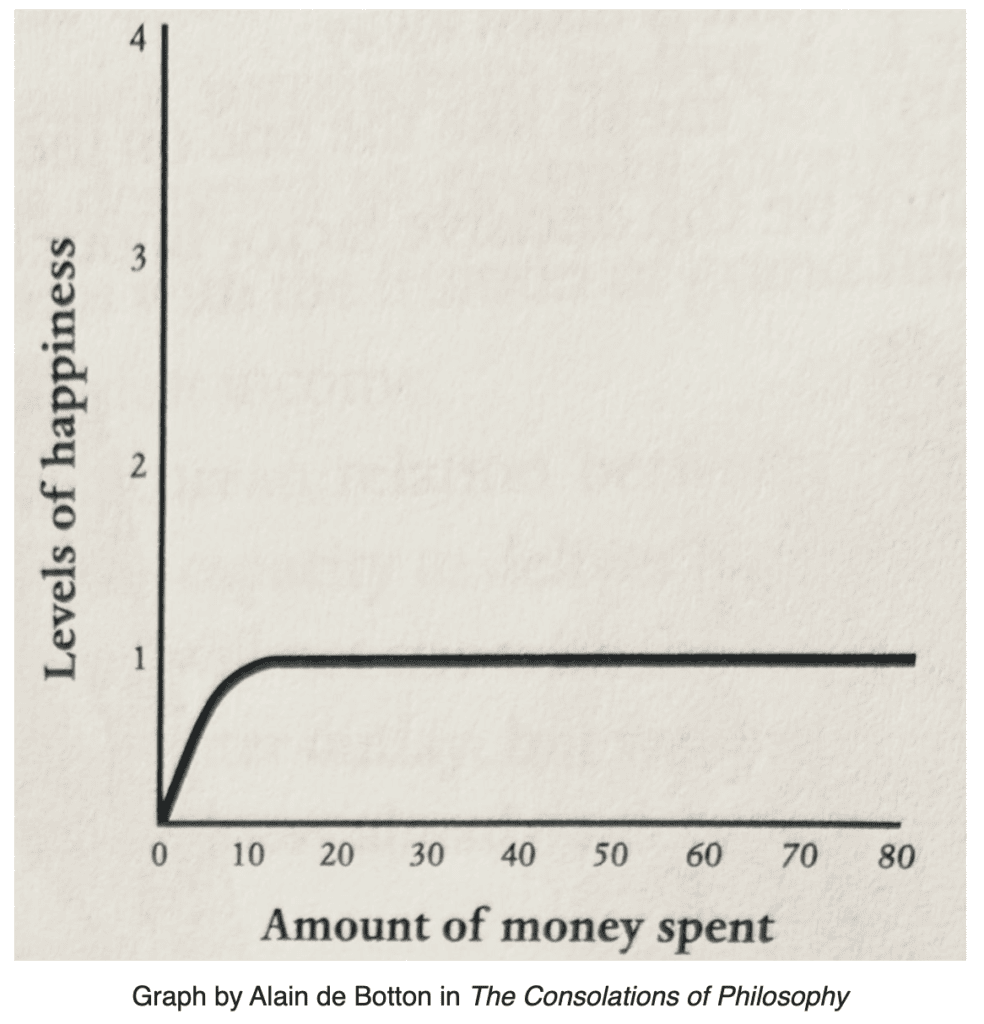

11. A contented state of being is the most sustainable form of happiness. Epicurus placed pleasure into two categories: active and static. Using food as an example, active pleasure is the pleasure you get from eating. Static pleasure is the pleasure of no longer being hungry. Epicurus believed static pleasure to be superior. When it comes to eating, the ultimate goal is not more pleasure from more food (active), but the contentedness of not being hungry (static). Active pleasures create a desire for more, meaning there’s never enough. Static pleasure is at total peace in and of itself.

12. I’ve been thinking about a quote of Stephen Marche’s every time I want to end my workout early: “Without struggle there is the struggle of no struggle.”

Books Read

-I read Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann and wow. Wow, wow, wow. In the 1920s, members of the Osage Nation in Oklahoma were mysteriously killed, one by one. It’s a shocking true story of greed and betrayal. I audibly gasped a few times while reading. Like the book Dead Wake (see below), it’s the perfect mix of history and suspenseful storytelling.

–What I Talk About When I Talk About Running by Haruki Murakami. I LOVED this book. It’s a memoir centered on running and how it facilitates his writing. Making a living as a novelist for more than 40 years takes an incredible amount of stamina. Most authors write a novel or 2, then move on to something else; life as a novelist is too hard to sustain. Murakami credits his career longevity to the physical limits he pushes himself to through running. I found the book inspiring and a kick in the ass to push myself harder during my runs.

-After reading The Splendid and the Vile last month, I became an Erik Larson fan. This month I bought and read Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania, and oh my gosh, it was so good. One of the things I love about Larson’s writing is the anecdotes he uses: a person’s frivolous yet telling quirks, the personal struggles of famous men and women, etc. Maybe the best of what he includes is the stuff he personally found most interesting. Like all good writing, his works center on the people, not just the events. On the why behind the what. This book also reads with such slow-building suspense that I had difficulty putting it down.

–Be Useful: Seven Tools for Life by Arnold Schwarzenegger. I was skeptical about reading this book, but I’m glad I did. It centers around this idea: be useful. Whatever you’re doing, be useful. If you don’t know what to do next, be useful. Your definition of being useful may be different than someone else’s, but that doesn’t matter. Be useful. Another message I got: you don’t have to always default to paying your dues. Sometimes you have to make a giant leap. (When he was just starting in movies, Arnold didn’t go for little parts here and there, he went for the starring role. In politics, he didn’t run for mayor or city council; he went straight for governorship.) Another message I liked: “Break the mirror”. Know the face of your neighbor better than your own. Focus your attention outward, on helping others. Inward focus is important too, of course, but the underlying reason to become personally successful (a reason I also firmly believe), is not so you can buy a larger house or take more vacations, but so you can do the greatest amount of good for the greatest number of people. This is the best reason for wanting to succeed.

-I loved Haruki Murakami’s book on running and writing so much that I decided to read another book of his, this one on just the writing: Novelist as a Vocation. I loved it. LOVED it. He writes so candidly and honestly that reading him feels like you’re reading a letter from a friend. And it’s filled with wisdom about writing.