These are the best books I read in 2025

I love to read.

What a beautiful gift—the ability to read. To be rewarded so vastly for a few hours of your time and attention.

It almost isn’t fair how easy it is! Open a book, let your eyes move over the lines, and bam—the world’s wisdom is yours.

What a beautiful gift a good book is.

The pages… the sentences…

The words.

One after another they chip away at our ignorance—our discontentment—and return us at once to stillness. We breathe a sigh of relief.

The stories.

One after another they pile up, pushing us away from the center of the universe, expanding our world as we’re brought down to size. We’re humbled and empowered. We become fearless.

How life-changing a good book can be. What a beautiful life we can build from them. (I keep a growing list of my favorites, which you can view and bookmark here.)

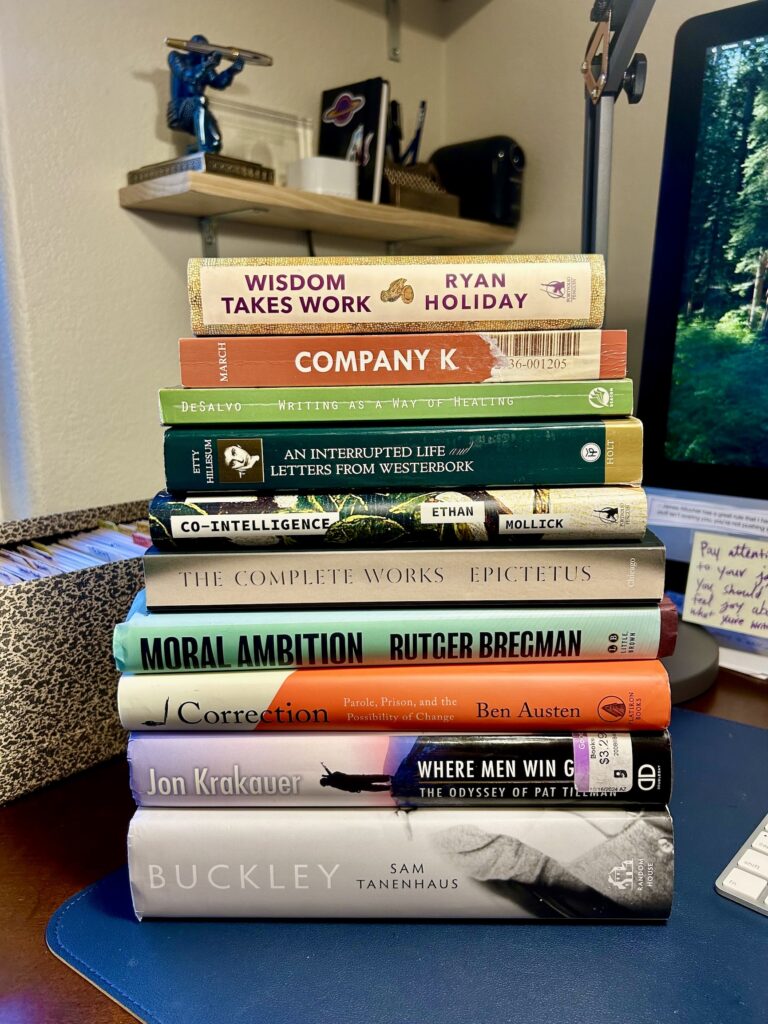

I read around 70 books this year, and many of them were among the best I’ve ever read. There were some that I couldn’t stop talking or thinking about, so I had to put them in a list and recommend them to you. These are the books that most changed the way I think, taught me something invaluable, and pushed me to be a better person. I have a feeling they’ll do the same for you.

An Interrupted Life and Letters from Westerbork by Etty Hillesum

One of the best discoveries I made this year was the writings of Etty Hillesum. How had I never heard of her?

Etty was a Dutch Jew living in Amsterdam when she began her diary—at her therapist’s urging—nine months after the Nazis took over the Netherlands. She was 27 years old. Two years later, at age 29, she would be murdered in Auschwitz, along with her family.

This book is made up of those diary entries and letters. Within them, we witness a startling personal transformation that unfolds over just two years.

In the early pages, we meet a young woman in emotional chaos: boy-crazy, prone to self-indulgent daydreaming, keenly aware that she spends too much time gazing at herself in the mirror. But as time passes, something remarkable happens. She begins to transform—spiritually, emotionally, philosophically—all in the face of unthinkable horror.

It’s as if the bleaker her circumstances became, the stronger her spirit grew.

While stationed with her family at Camp Westerbork, Etty describes walking beside the barbed-wire fences and feeling… joy. She wasn’t delusional. She understood what would likely happen to her. Yet that awareness did not lead her to despair. In fact, the opposite occurred: she fell more deeply in love with life.

And here’s the thing—she could have gone into hiding. She chose not to.

Defying her friends’ pleas, Etty refused to hide from her persecutors. “She didn’t want to desert her parents, but more than that,” Carol Lee Flinders writes, “it just felt morally wrong to her that anyone would concentrate on personal survival who could be reaching out lovingly to others instead.”

Friends even recall failed attempts to “kidnap” Etty and put her into hiding. Convinced she didn’t fully understand the danger she was in, Klaas Smelik—the writer to whom she would later entrust her diaries—once grabbed her in an attempt to pull her to safety. She wriggled free, stepped back, and said, “You don’t understand me.” When he admitted that he didn’t, she replied: “I want to share the destiny of my people.”

In that moment, he knew there was no hope of “rescuing” her. She would not allow it. Besides, she argued, what did it matter if she went—or if someone else did?

And this was a woman who had everything going for her! She had family and friends, a law degree, ambition, curiosity, and a full, vibrant inner life.

Yet she would not run and hide—not when there were so many people right in front of her she could help.

I could go on and on. Whenever someone asks me if I’ve read anything good lately, this is the book I talk about. Do yourself a favor and read it!

(And if you want an even deeper dive into Etty Hillesum, I’ve read and recommended Etty Hillesum: A Life Transformed by Patrick Woodhouse, Enduring Lives: Living Portraits of Women and Faith in Action by Carol Lee Flinders (the section on Etty), andThe Jungian Inspired Holocaust Writings of Etty Hillesum: To Write Is to Act by Barbara Morrill, and the textbook, Reading Etty Hillesum in Context.)

Wisdom Takes Work by Ryan Holiday

Not only is this one of the best books I’ve read this year, it’s one of the best books I’ve read, period. It’s also my favorite book in his virtue series.

This book is about the most important kind of knowledge there is: knowing what’s what. What’s worth pursuing. What we should avoid. What we can ignore. What we should never ignore.

Lots of people are smart—but how many have wisdom? Lots of people know facts, but how many can think with nuance? How many people really know themselves? (Self-awareness, he argues, is the rarest thing in the world.)

“Think of the people,” he writes, “who […] miss out on life because they are chasing immortal fame.” They convince themselves that their job is so important they don’t have time for contemplation, or even an hour with a good book. They check their work emails well after they’ve logged off for the day. They do things that could have gone without doing.

“Wisdom is knowing that what you do is important…but that it’s not that important.”

In doing all this, they miss the whole point of life: happiness. Not pleasure or comfort, but the deeper happiness that comes from doing the right thing, for the right reasons, in the right way, at the right time. The happiness that comes from truly knowing what’s what.

And this kind of wisdom takes constant effort. Famed basketball coach George Raveling, Holiday writes, “wakes up each morning, sits on the side of the bed, and gives himself two choices. ‘George,’ he says to himself, ‘you can either be happy or you can be very happy.’”

“Wisdom is happiness. Happiness is wisdom,” Ryan writes. “This is not a tautology. No one would be happy not fulfilling their potential, and yet, can one flourish without joy and happiness?”

This is another book I could go on and on about. It’s that good. Do yourself another favor and read it.

Moral Ambition by Rutger Bregman

I didn’t think I would like this book. I assumed it would be another familiar argument about how we should stop chasing money and things and start caring more about making the world better.

And yes—it is that book. But it’s also so much more. It’s genuinely inspiring and eye-opening. Even my wife, Courtney—who typically blasts scream core while she cooks—turned the music off each evening so I could read it out loud until we finished it.

The thought experiment that made philosopher Peter Singer famous goes like this: suppose you’re on a walk and see a child drowning in a pond. You want to jump in and save the child, but then you remember you’re wearing a pair of brand-new, super expensive shoes. Jumping into the pond would ruin them. What do you do?

Obviously, you save the child. Pose this question to anyone and the answer is always the same. What kind of question is that, anyway?

But Singer argues we do the exact opposite all the time. The money we spend on things we don’t need could save so many children’s lives.

One of the stories I loved was that of businessman-turned-philanthropist Rob Mather. After finding the success of a corporate career deeply empty, he wanted to put his energy toward something that actually made a difference. But what? He wasn’t interested in a vague gesture or a symbolic cause—he wanted to take on a problem that was massive, yet solvable. He found malaria.

In 2005, malaria was killing 3,000 children every day. That’s the equivalent of seven jumbo jets full of children going down. It’s almost impossible to fathom. Could one person really do something about that?

As it turns out, malaria has a surprisingly simple and inexpensive solution: mosquito nets treated with insecticide. So Rob decided he would raise money to provide them.

But this raises an obvious question. If curbing such a deadly disease is really that straightforward, why hadn’t someone already done something about it?

That’s one of the many questions Bregman urges us to sit with. Even the tiniest effort on our part, he argues, can make an extraordinary difference. “You can be your average exec in your average company one day and then take the lead in fighting one of the world’s deadliest diseases the next.”

Mather went on to found the Against Malaria Foundation, which has now “raised more than 700 million dollars and distributed over 300 million mosquito nets to 600 million people.” Because of this, the daily death toll has dropped from the equivalent of seven jumbo jets to fewer than three.

In one village in Uganda’s West Nile region—where nearly half the population had suffered from malaria in the preceding months—Rob’s foundation distributed 50,000 mosquito nets. A man from the village later walked six miles to dictate a message through the Red Cross to Rob, letting him know that malaria no longer existed there. The disease had been completely eradicated in his village.

It’s such an inspiring and timely book. Courtney and I loved it.

More books that made this year of reading especially rich:

Correction: Parole, Prison, and the Possibility of Change by Ben Austen

This was so moving and well-written I remember holding it to my chest after reading certain passages.

Company K by William March

This is phenomenal and I wrote about one of my favorite stories from it here.

Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI by Ethan Mollick

This was essential to understanding Chat GPT and how to use it as a creativity partner.

Writing as a Way of Healing by Louise DeSalvo

I underlined or starred something on almost every page.

Buckley: The Life and Revolution that Changed America by Sam Tanenhaus

I read this to better understand Charlie Kirk and his motives for saying the things he said. (By the way, this is another benefit of reading good books: so you can hear messages like Charlie’s and not think they’re normal.)

Epictetus: The Complete Works Robin Waterfield

Literally incredible. It’s like a cleanser for your mind, washing away the mental weeds and tuning your thoughts to the sound of reason.

Where Men Win Glory by Jon Krakauer

I finished this recently and Oh. My. Gosh. It is so, so good.

Narrowing down the above list was tough, so here are other books I read this year and loved:

Philosophy as a Way of Life by Piette Hadot, 1984 by George Orwell,The Mind on Fire by Robert D. Richardson, Etty Hillesum: A Life Transformed by Patrick Woodhouse, The Art of Slow Writing by Louise DeSalvo,Fahrenheit 182 by Mark Hoppus, Transcendentalism and the Cultivation of the Soul by Barry M. Andrews, Abundance by Ezra Klein & Derek Thompson, Still Writing by Dani Shapiro, Address Unknown by Kathrine Kressmann Taylor,Writing My Wrongs by Shaka Senghor, The Inner Game of Tennis by W. Timothy Gallwey, How To Think Like Socrates by Donald J. Robertson, Enduring Lives: Living Portraits of Women and Faith in Action by Carol Lee Flinders, The Autobiography of Malcolm X by Malcolm X, The Stranger Beside Me by Ann Rule, How To Be Caring by Shantideva, Lincoln on Leadership by Donald T. Phillips,The Courage To Create by Rollie May,History Matters by David McCullough, American Kings: A Biography of the Quarterback by Seth Wickersham, Socrates by Paul Johnson,With the Old Breed by E. B. Sledge,A Marriage at Sea by Sophie Elmhirst, New Seeds of Contemplation by Thomas Merton, How To Be Caring by Shantideva, and Into the Wild by Jon Krakauer.