There’s a story about Socrates’ teenage son, Lamprocles, who complained bitterly that his mother—Socrates’ famously fiery wife—nagged him nonstop.

Socrates, ever the philosopher, gently questioned his son until he admitted she was a loving mother who had his best interests at heart. Even so, Lamprocles maintained he couldn’t stand the constant scolding.

Then Socrates asked a question that, according to cognitive-behavioral psychotherapist Donald J. Robertson, was nothing short of ingenious: “Do actors in tragedies take offense when other characters insult and verbally abuse them?” He notes that the insults hurled onstage were far worse than anything Lamprocles’ mother ever said.

The boy thought this was a silly question. It was obvious they didn’t take offense. The actors knew it was only a performance; no real harm was intended.

“That’s correct,” replied Socrates, “but didn’t you admit just a few moments earlier that you don’t believe your mother really means you any harm either?”

With a few well-placed questions, as Robertson writes in his wonderful book How to Think Like Socrates, “Socrates helped Lamprocles to examine his anger from a radically different perspective. When assumptions that fuel our anger begin to seem puzzling to us, our thinking can become more flexible, and we may begin to break free from the grip of unhealthy emotions.”

So, what if we got better at leaving things uncertain? What if we stopped rushing to judgment?

This kind of perspective shift is easier when the challenge is circumstantial. When plans fall through, when a door closes, when life doesn’t go as expected, we can take a breath and trust that time will reveal meaning. We remind ourselves that life often has its reasons.

But bringing that same calm to our relationships is harder. When someone’s words sting or their actions feel unjust, detachment doesn’t come naturally. We’re wired to take things personally, to collect evidence for our hurt, to seek justice.

And yet, as Socrates reminded his son, what we see on the surface is rarely the whole truth. We don’t know the full story playing out behind someone’s eyes. Pausing to hold space for that mystery softens us, makes us kinder. That softness is not weakness but wisdom. Clarity.

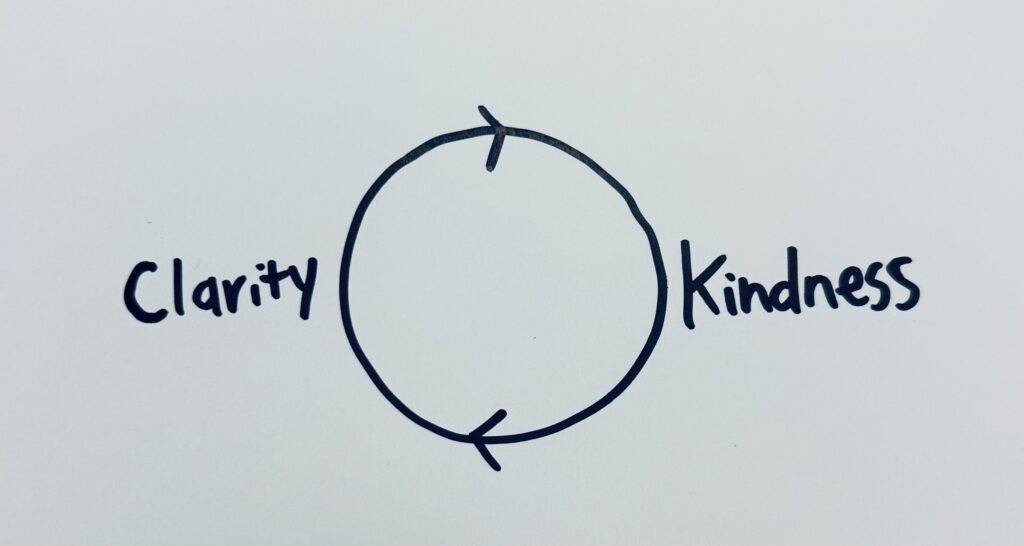

And clarity and kindness are inseparable.

It’s like that bit of Chinese wisdom: Clarity can be obtained only in a kind person. A person can be kind only with clarity.One helps the other.

One of the most haunting, beautiful stories I’ve ever read about appearance versus reality comes from William March’s masterful novel, Company K—a mosaic of war stories in which each chapter is a different soldier’s account of the front lines.

Private Allan Methot, once an aspiring poet, complained that the “spiritual isolation” of army life was unbearable. He couldn’t talk to anyone. No one could understand him. His fellow soldiers repulsed him—they seemed to care only about food, sleep, alcohol, and women.

As if that weren’t bad enough, he was assigned night watch duty with Private Danny O’Leary—whom he found hopelessly dull.

Methot wrote that O’Leary’s eyes were “unlit by intelligence” and that “he would stand there stupidly and stare at me, his heavy brows drawn together, his thick lips opened like an idiot’s.” Any attempt at conversation was futile. When Methot spoke to O’Leary, “he lowered his eyes, as if ashamed of me, and stared at the duckboards, fumbling at his rifle. . . .” When O’Leary finally spoke, it was to ask Methot when he thought they might get paid.

Methot laughed in contempt. How alone he was! It was as if he lived among aliens. His account ends in despair. He climbed out of the trench and walked slowly toward enemy lines, reciting poems aloud, waiting for the moment when a soldier’s boot would crush his “frail skull.”

And then, in the very next chapter, came Private Danny O’Leary’s letter to Methot.

In it, O’Leary wrote that Methot’s poems were the most beautiful thing he had ever heard. He thanked Methot for his friendship, saying that his faith in him had changed his life.

His letter is so devastatingly beautiful that it’s worth writing in full:

“I would like you so see me now, Allan Methot: I would like you to see what you have created!—For you did create me more completely than the drunken longshoreman from whose loins I once issued.

I was so gross, so stupid; and then you came along—How did you know? How could you look through layer upon layer until you saw the faint spark that was hidden in me? . . . Do you remember the nights on watch together when you recited Shelley and Wordsworth?—Your voice cadencing the words was the most beautiful thing I had ever heard. I wanted to speak to you, to tell you that I understood, to let you know your faith in me would not be wasted, but I dared not.—I could not think of you as a human being like myself, or the other men of the company. . . . I thought of you as someone so much finer than we that I would stand dumb in your presence, wishing that a German would jump into the trench to kill you, so that I might put my body between you and the bullet. . . . I would stand there fumbling my rifle, hoping that you would speak the beautiful lines forever. . . . ‘I will learn to read!’ I thought. ‘When war is over, I will learn to read! . . .’

Where are you now, Allan? I want you to see me.—Your friendship was not wasted; your faith has been justified. . . . Where are you, great heart? . . . Why don’t you answer me?”

Whoa.

As I mentioned, this story really stuck with me. Whenever I talk with someone now—the cashier at the grocery store, a friend, my brother—I try to imagine the boundless intelligence and light behind their eyes. The infinite treasures and possibilities just below the surface.

The paradox is that what’s most mysterious—uncertain, unlabeled, unknown—is often what’s most real. It’s what most closely resembles life itself.

I try to remember that clarity is probably more about what I cannot see than what I can.

And somehow, that simple truth—that I know so little—makes me calmer, kinder, and happier.