What does money have to do with happiness?

It’s a tricky question.

Luckily for us, Epicurus, one of the wisest philosophers to have ever lived, thought a lot about it. And he had a lot to say.

To start, Epicurus defined happiness as not being in active pain, physically or psychologically.

To remedy physical pain, the answer is pretty straightforward. We need money for things like food, clothes, and shelter.

To remedy psychological pain, however, the answer isn’t as clear-cut. Because of this, Epicurus spent more time addressing this pain. Anxiety, superstition, and fear are often self-inflicted. Meaning they’re mostly in our control.

The gist of his philosophy was this: as long as you’re not in pain, you have everything you need to be completely happy. Our emotional disturbances stem from how we see the world, which we can change at any moment.

When it comes to money, Epicurus said, sure, it can make you happier, but only if you already have 3 things money can’t buy: friends, freedom from the need to impress others, and a reflective life.

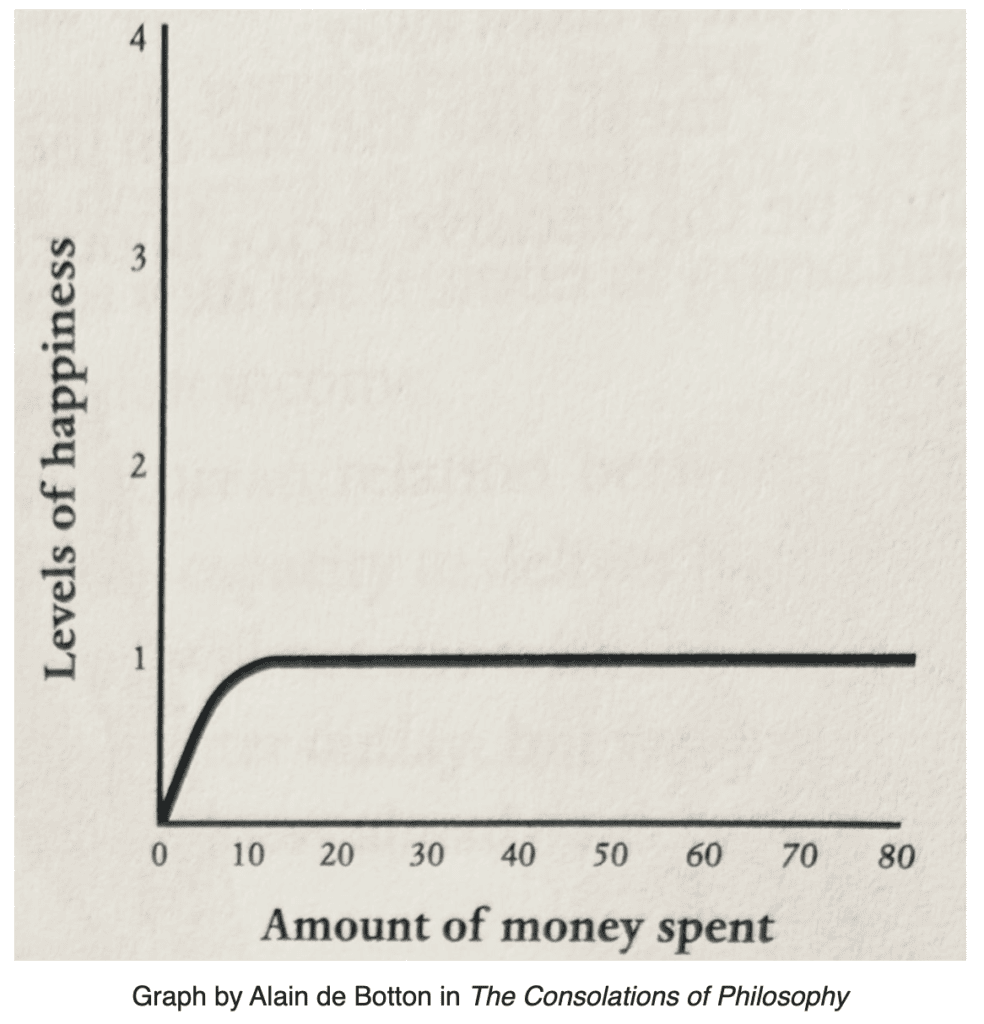

Here’s a graph showing the correlation between money and happiness for a person without friends, freedom, and thought:

It’s important to note too that Epicurus said even with these 3 things and a lot of money, your level of happiness will never surpass what’s already available on a limited income.

Let’s examine these 3 things a little closer:

Friends

Take this thought experiment (paraphrased from Alain de Botton’s wonderful book The Consolations of Philosophy): Identify an idea for happiness. For example, In order to be happy on vacation, I need to stay at a luxury resort. Imagine that this idea might be false. Look for the exceptions between the supposed link to happiness and the desired object in the original statement. Could I spend money on a luxury resort and still not be happy? Could I be happy on vacation and not spend as much money on a resort? If an exception is found, the desired object (a luxury resort) cannot be a sufficient cause of happiness. It’s possible to have a miserable time at a luxury resort if, for example, I feel friendless and isolated. It’s possible to be happy in a tent if I am with someone I love and feel appreciated by. Now we can change the original statement to include these nuances. My happiness at a luxury resort will depend on being with someone I love and feel appreciated by. I can be happy without spending money on a luxury resort, as long as I am with someone I love and feel appreciated by. Our final statement for what would bring happiness is now different from the confused one we started with: Happiness depends more on having a congenial companion than staying at a fancy resort.

Freedom

“I wonder how many people would seek excessive wealth,” Nassim Nicholas Taleb mused, “if it did not carry a measure of status with it.” It makes you think. Finance writer and author of the amazing book The Psychology of Money, Morgan Housel said when it comes to money, everyone needs basics. Once those are covered, there’s the next level of comfortable basics. Past those are the basics that both comfort, entertain, and enlighten. “But spending beyond a pretty low level of materialism,” he says, “is mostly a reflection of ego approaching income, a way to spend money to show people that you have (or had) money.” He says if we want to increase our savings, we don’t need to raise our income, we need to raise our humility. A lack of humility won’t just hurt us financially, but emotionally as well. Without humility, life can become an endless chore of keeping our peacock feathers fully extended, trying to keep up with other people who are doing the same. It’s nothing new, though. Epicurus, born in 341 BC, saw this same human impulse. That’s why he warned against it. He saw how unhappy people became when they chained their identities to their finances. If our goal is to live happily, what sense does it make to get worked up over trivialities, such as vanity, since doing so would compromise our goal to live happily? If we never feel like we have enough, we will never be free. The great news is that freedom from this (and almost everything else) requires only a change in perspective. Your freedom is worth that much, right?

Thought

A person prone to worry will worry regardless of how much money she has. To the anxious mind, more money doesn’t solve problems, it just creates new ones. As Seneca put it, “One needs another happiness to safeguard the happiness one has; prayers need to be made on behalf of prayers already fulfilled.” He tells the story of a wealthy man he knew, Vedius Pollio, who went into such a rage when a slave dropped a tray of crystal glasses during a party, that Vedius ordered the slave to be thrown into a pool of vampire fish. “The possession of the greatest riches,” Epicurus said, “does not resolve the agitation of the soul nor give birth to remarkable joy.” Material things can’t unburden you. So what can? Modern psychology agrees with Epicurus: one of the best ways to combat worry is with thought. Specifically, rational analysis. It’s why journaling is one of the best (and most cost-effective) forms of therapy available. A reflective life is a good life. And a good life is a happy life. And a happy life, as we’ve seen, has little to do with money.

Alain de Botton beautifully summarized Epicurus’s point: “If we have money without friends, freedom, and an analyzed life, we will never be truly happy. And if we have them, but are missing the fortune, we will never be unhappy.”

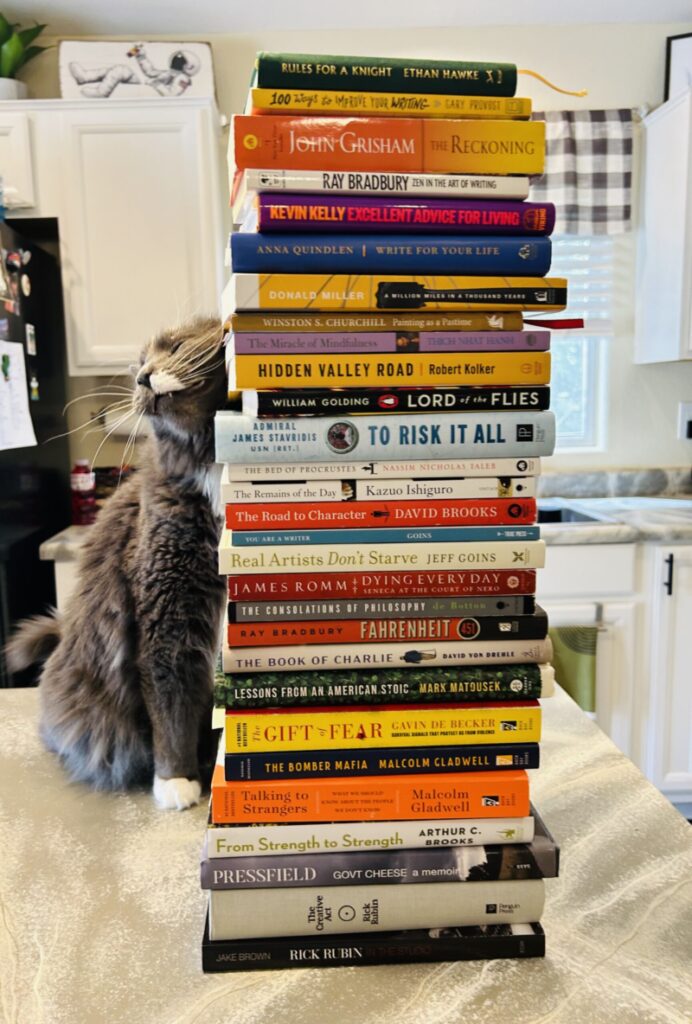

Books Read This Month

-In 1959, four members of the Clutter family were brutally murdered in their home in Holcomb, Kansas. In In Cold Blood, reporter Truman Capote narrates this unsettling story while also diving into the lives and minds of the family’s ruthless, complex killers. I had a hard time putting this book down, so I wasn’t surprised to see that it’s ranked in Modern Library’s 100 Best Nonfiction Books of all time.

-In Feynman’s Rainbow, Leonard Mlodinow recounts his first year as a staff member in the Caltech physics department—and his interactions with the quirky, famous, brilliant physicist Richard Feynman. Mlodinow shares the advice Feynman had given him on science, creativity, careers, and life. There’s such great stuff in here. (I also loved Feynman’s autobiography, Surely, You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman.)

-A friend recommended Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematory by Caitlin Doughty and I LOVED it. This girl is hilarious. (I read a part to my wife while we were getting ready for bed and she prematurely spit out her Listerine.) Doughty says we, as a society, need more exposure to the topic of death, to be more comfortable talking about it, because it’s all around us and part of life. Reading this book has alleviated my superstitious phobia of the topic. And not to be intense but I feel liberated in a way. So much so that I’ve ordered 2 more books about death that I’ve heard great things about: Stiff by Mary Roach and All the Living and the Dead by Hayley Campbell.

-I had the book Tiny Beautiful Things by Cheryl Strayed on my bookshelf for years. While deciding what to read next, I picked it up to skim. Fifty pages later and I was kicking myself for not reading it years ago. No wonder this book has been recommended by so many people I admire! It’s basically an advice column in book form, and Strayed gives the WISEST advice. I asked my non-reader wife if I could read a chapter to her and she said sure (in the polite kind of way you say sure when someone asks you if you want to see pictures of their kids). But when I had finished reading the chapter, she asked me to read another. She even grabbed the book out of my hands a few times to take notes. Just a great book that I’ve learned so, so much from.

-I first read Ego is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday in 2016 and it completely changed my worldview. I read it again this month and was reminded why it’s one of the best books I’ve ever read. We waste so much of our lives chasing things we don’t care about, doing things we don’t want to do, trying to impress people we don’t respect. That’s ego. Ego cares about the title, not the job. It cares about posturing, not purpose. Ego wants it all. It wants a wife and a mistress. It demands recognition and praise. But ego is not real. It’s smoke and mirrors of the worst kind. And sadly, too many people learn this far, far too late.

–How to Have a Life: An Ancient Guide to Using Our Time Wisely is a new translation of Seneca’s On The Shortness of Life, one of my top 3 favorite books of all time (alongside Meditations and The Daily Stoic). It answers some of the deepest questions: What’s worth pursuing in life? How do we seize the time we have so it doesn’t flee past us? What things can we rightfully say no to? How do we stop arrogantly putting things off into the future, as if we’re sure we have endless days ahead of us? What I love about Seneca’s writing is how easy it is to read, how it feels like reading a letter from a friend, not some guy who lived 2,000 years ago. If you haven’t read this book already, you need to. You won’t regret it.