Commit once and for all

About a month ago, a new policy was announced at work.

It wasn’t anything crazy, but I was annoyed, and I complained to Courtney and my parents. The more I thought about it, the more miserable I made myself.

A few weeks later, I was notating Epictetus’s Enchiridion.

“You want to win at the Olympics? So do I—who doesn’t?” Epictetus said to a student. But before you jump in, reflect on what that entails: you’ll need to adopt a strict diet, a brutal exercise regimen, and submit completely to a trainer. Your ankles will likely swell. You’ll sustain injuries and swallow mouthfuls of sand. Oh and after all that you still might lose.

If, after considering everything you’ll have to do, you still want to be an Olympian…then do it wholeheartedly, he said. Don’t pause to think about it or you will end up jumping from one infatuation to the next. You’ll be like a child; one day they want to be a gladiator, the next day a musician, the next an actor, and so on. Give your pursuit sincere attention and commit with all your heart.

He then applies this lesson to life.

You claim to want serenity and freedom and peace, but are you willing to pay the price? Are you willing to change the way you eat and drink? Are you willing to put up with nights of pain? To be criticized? To forfeit status and power? Willing to moderate your desires and aversions? To be okay with getting the small end of the stick in even the tiniest matters? In a word, are you willing to live as a philosopher?

If you’re unwilling, don’t go near it, he says. Walk away. You can’t be a philosopher one day and someone else the next. You can only be one person. Make your decision, and commit once and for all.

This struck me with a force that’s hard to describe.

You say you want freedom, yet here you are, troubled.

Commit once and for all.

Every day the next week, I wrote, “Commit once and for all” on the back of my hand. I took a thick, black Expo marker and scrawled the phrase on the bathroom mirror. I needed reminders. I had been using philosophy in some parts of my life, but clearly not in others.

One of my favorite passages from Epictetus is where he says if people truly grasped how short life is, they would never entertain miserable thoughts. He didn’t say they would never entertain a miserable thought unless something seemed unfair, or unless a situation felt overwhelming, or unless someone pissed them off. They just wouldn’t entertain those thoughts, period.

It’s important to note that he wasn’t talking about negative thinking, which we know can be used, paradoxically, to increase positivity. He was talking about thoughts that do nothing but make you feel miserable.

Epictetus spent the first 30 years of his life as a slave. One day, his master, feeling especially cruel, grabbed Epictetus’s leg and began to twist it. “If you keep doing that,” Epictetus told him, “you’re going to snap it.” The master kept twisting. Epictetus’s leg snapped. “See,” Epictetus said calmly. “I told you that would happen.”

It’s not that Epictetus didn’t feel pain. Of course he did. But his philosophy said things outside of his control could not harm him. That his leg is broken? That is objectively true. That he’s harmed by it? That was up to him. And his commitment to his philosophy was greater than his broken leg.

Seneca had a respiratory illness that sometimes made it hard to breathe. When it flared, he would spend days in bed, in a state of near suffocation. Writing about these experiences to his friend Lucilius, Seneca said that even though his body was in anguish, his mind was at ease. “Even while suffocating,” he reflected, “I did not stop resting serenely in brave and cheerful thoughts.” The Epicurean philosopher, Epicurus, was in excruciating pain on what he knew would be (and was) his last day on earth. Still, he wrote that he felt a “gladness of mind” by recalling pleasant memories of conversations with friends.

Like Epictetus, Seneca and Epicurus were not immune to pain. In fact, their empathetic natures probably amplified their pain at times. But here they were, nearly suffocating and dying, still committed to their philosophy, still not letting outside things harm them, still feeling “gladness of mind”. Not in a “toxic positivity” way—they weren’t smiling and saying, ‘Aw gee, shucks, isn’t this great?’—but in the contented way that comes from soberly processing negative emotions and calmly accepting what they could not control.

These were people who were committed. This is who they were; the situation wouldn’t change them.

Commit once and for all. This was my wake-up call and a reminder that I can’t pick and choose where I use philosophy. Like an Olympic athlete, I must be totally committed.

So a policy changed at work? And? Why are you thinking about it now anyway? It doesn’t take effect until next year. Besides, think of how lucky you are to have this job and the wonderful people you’ve met because of it.

You’ll find a way to use this to your advantage. You’ll see it’s for the best.

P.S. It turns out the new policy won’t change things that much. This brings to mind another stoic principle I had disregarded: don’t suffer before it’s necessary or you’ll suffer more than is necessary. But more on that another time.

P.P.S. Courtney woke up to my mirror reminder. She sent me this pic while I was at work, saying it had scared the shit out of her.

Books Read

-I loved The Devil in the White City by Erik Larson. It’s a story about the Chicago World’s Fair, the architects who built it, and the serial killer who used it to lure his victims. What makes it even creepier is that it’s true.

–How To Do the Right Thing by Seneca was great. It’s part of the Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers series, a collection of books that take individual philosophers’ works and piece together writings on a narrow topic. Other books of theirs I’ve enjoyed: How to Be Free, How to Keep Your Cool, How to Be a Leader,How to Be a Bad Emperor, How to Give, How to Be Content.

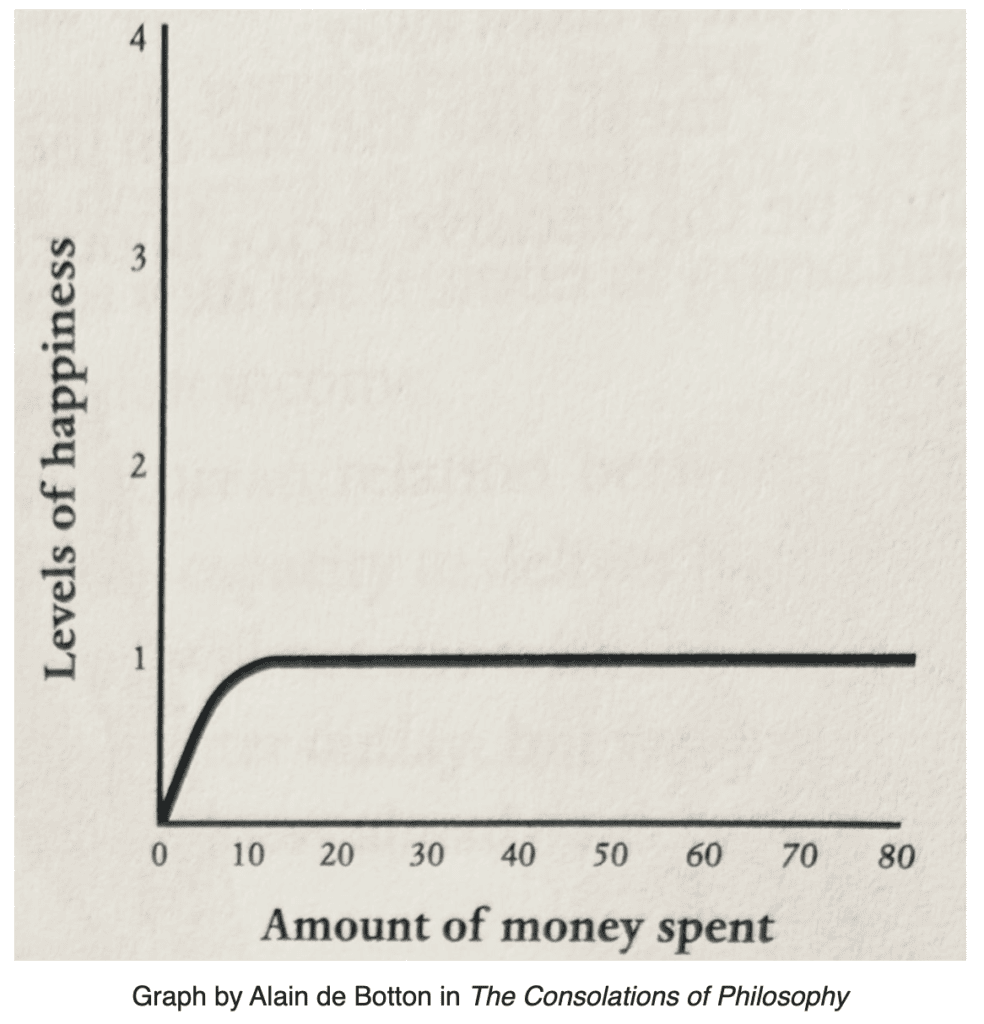

-I loved Morgan Housel’s The Psychology of Money, so I preordered and read his newest book Same as Ever, a collection of stories about what doesn’t change. I found some great reminders: the better story wins, risk is what you don’t see, the magic of compounding. Other topics that made me think: the importance of imperfection, the short lifespan of competitive advantage, and the simplicity of most things (and how and why we complicate them).

-I was hesitant to read Elon Musk by Walter Isaacson because I wasn’t sure how transparent it would be. But then I saw that Isaacson referred to Musk as a man-child, and I dove right in. Wow…this is one of the best books I’ve read this year. It’s an up-close view of how one of the most wildly successful entrepreneurs operates and makes decisions. It made me see Musk in a new light. I had a hard time putting it down. A very hard time. The short chapters and loads of pictures made it a fast read too. I didn’t want it to end.