Why success is simpler to achieve than you think

A turning point in my life came when I realized that success is not measured by external accomplishments.

Success is measured by my choices.

What did it matter that I was a top performer at work if I was still smoking cigarettes? If I was always stressed out? What was the point of knowing the ins and outs of my industry if I still didn’t know myself?

We spend so much time thinking about what other people are thinking or doing. We worry about how things are going to turn out. We think we have to do everything right away. Then we wonder why we can’t get anything important done! We wonder why we feel stuck.

Marcus Aurelius said sanity means tying your well-being to your own actions. And being satisfied with even the smallest progress. Circumstances and people can obstruct your path, sure, but nothing can impede your will or disposition. Nothing can stop you from adapting, from using obstacles as fuel. “As a fire overwhelms what would have quenched a lamp,” Marcus said. “What’s thrown on top of the conflagration is absorbed, consumed by it—and makes it burn still higher.”

It was this realization—the realization that no one could hinder me, that no obstacle could keep me from taking the next most appropriate step in my life—that gave me clarity. I went back to school in my late twenties. No one could stop me from taking one class, and then the next. I got my degree in half the time. I quit smoking.

When I started focusing on my own actions, and taking it one step at a time, that’s when things changed.

Internal Focus = Freedom

In 1981, the young physicist Leonard Mlodinow accepted a postdoctoral fellowship at Caltech University. On his first day, the physics department chairman pulled Mlodinow into his office. “We have judged you to be the best of the best,” the chairman said to him. Because of this, Mlodinow could work on whatever he’d like. He could teach. Or not teach. He could design sailboats. It didn’t matter. Whatever he chose to work on, the chairman said, was bound to be important. Mlodinow was much less confident. He felt tremendous pressure. What should he do? What was important to him? String theory was popular, should he devote himself to that? He liked to write, should he be a writer? Frustrated, he sought advice from the famous Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman, who worked down the hall. As the academic year progressed, Feynman offered Mlodinow advice and challenged his thinking. Still, he was lost. People were depending on him to do great things! And he had no idea where to start. After about a year of working alongside Feynman, Mlodinow began to understand why he had been having so much trouble finding a direction: his focus was external. “I had gone through college and into academia in a hurry,” he said, “wanting to rush ahead with my work, to prove to the world that I had been alive, and that it had mattered.” He had been stuck, he said, because he thought worthy goals were meant to “accomplish and impress”, and that he needed to be considered as “an important person, and a leader.” But Feynman’s example showed him a different way. Feynman “didn’t seek the leadership role. He didn’t gravitate to the sexy [popular] theories. For him, satisfaction in discovery was there even if what you discover was already known by others. It was there even if all you are doing is re-deriving someone else’s result your own way. . . . It was self-satisfaction. Feynman’s focus was internal, and his internal focus gave him freedom.” Mlodinow realized that he didn’t need to live up to other people’s expectations. He may not achieve the conventional or material success that his parents had wanted for him, but (and here we can imagine him smiling as he wrote), “at least with an internal focus, my happiness would be under my own control.”

What You Get is Gradual Transition

Author and comedian Mark Schiff recalled a conversation he’d had with an old rabbi. The rabbi had spent most of his life studying the Talmud for hours and hours each day. “What bothers me most,” the rabbi said, “is that with all the studying I’ve done, I feel like I’ve only dipped the tip of my pinky into the well.” And that’s what it feels like sometimes, doesn’t it? We put in years of hard work and it feels like we’re standing in place. But of course, this is an illusion. We are making progress—it’s just hard to see against the backdrop of our infinite potential. Schiff points out that no one reaches his or her full potential. Why? Because our potential is so vast! The rabbi concluded, “I’ll just have to be satisfied [that] I’ve done the best I could do.” And that’s all any of us can do. There’s no perfection, no ultimate becoming. There’s just a continuous journey. Donald Miller pointed out how some people become depressed when they realize this. Unlike the movies, there’s no one grand climax in the script of our lives. There are climaxes in the subscripts—milestones hit, goals achieved—but there’s no one climax. The human journey goes on. In Aaron Thier’s novel The World is a Narrow Bridge, the characters go on a cross-country trip. They cross the Mississippi River and enter the beautiful, magnificent American West. “And yet,” Ryan Holiday observes, “everything seems the same. The same trees, the same scenery, the same air.” The human journey goes on. As Thier writes, “You wait for the big moment, and what you get is gradual transition.”

Internal Focus. One step at a time. Gradual transition. That’s success.

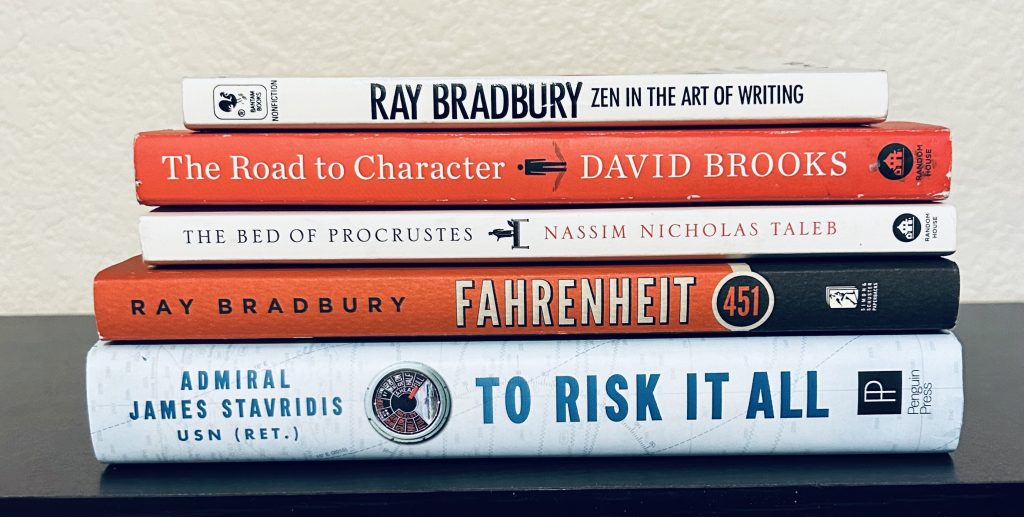

Books Read

–The Monster of Florence by Douglas Preston and Mario Spezi was wild…and disturbing. Basically, American journalist Douglas Preston and Italian journalist Mario Spezi decided to write a book about the never-identified serial killer who stalked and murdered young lovers between 1968 and 1985 in Florence, Italy. What makes the story even more unsettling is the web of corruption within the investigation—a web Preston and Spezi became caught in themselves.

-Each year, I reread Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, and I always find new takeaways. I ALWAYS feel lighter and happier afterward. The context of Meditations has been well-documented, but I’m compelled to reiterate it here because it’s the context that makes it so remarkable. Marcus Aurelius never intended for Meditations to be read by anyone—it was his private journal, full of admonishments, encouragements, and reminders he’d written to himself about how to live a good life, develop his character, and be of service to others. And here’s the thing: he was the most powerful man in the world. He could have done whatever he wanted! He could have indulged every desire and lived in comfort and luxury. Instead, his thoughts and actions were focused on doing the right thing and helping other people. He was the exception to the rule that “absolute power corrupts absolutely”. Named the last of the “Five Good Emperors”, Marcus Aurelius wrote Meditations 2,000 years ago, and it is still one of the most inspiring texts we have today on how to live a good, happy life.

-After reading The Consolations of Philosophy in May, I had been looking for more books by Alain de Botton. I searched his name on Amazon and found a book series he edits, The School of Life, and I bought and read How to Think More Effectively. I got so much from it. It’s made up of fifteen short chapters, each about a different way of thinking. I’m eager to go back through the book and notate the passages I marked and underlined. I also bought and look forward to reading The School of Life: An Emotional Education.

-From another book series I love, I bought and read How to Be a Stoic, a great little book with a few chapters from each of the 3 best books on Stoicism: Enchiridion, On the Shortness of Life, and Meditations.

-I bought The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz by Erik Larson over a year ago and finally got to reading it. And it’s as good as people say it is. The absolute best thing that I got from this book though was in the Sources and Acknowledgments section at the end. Larson tells us why he decided to add another book about Winston Churchill to the public collection, and how he made it different from all the rest.